With the triumph of Javier Milei in Argentina’s November 2023 national election, the country has followed the contemporary global trend of electing far-right governments. Through his frequent television appearances as an “economic expert”, Milei successfully mobilized voters against the country’s dominant political elites, which he denigrated as “la casta” (“the caste”). Ordinary Argentines, in this narrative, were being cheated and disserved by an elite class who benefited from a wasteful and inefficient state. Milei’s rhetoric, which solicited votes from workers and the poor, invoked a utopian vision of society driven by free competition between agents whose performance in markets is the only cause of their success or failure. In this vision, the capitalist market naturally rewards the best, while the “State” and other “collectivist” forms of what Milei deems to be “autocracy” corrupt the market and nourish what Milei labels “parasites”.

Through a virulent and aggressive discourse, the newly elected government and its followers have recoded social cleavages to divide and cast in opposition different sections of labor. Those employed by the State and by cooperatives, whose incomes come from social assistance, are deemed “lazy,” “useless,” and “unproductive” and are accused of taking advantage of “good people” who are oppressed by excessive taxes and regulations. Thus, cooperative “Popular Economy” organizations (known as piqueteros) and public sector workers (including teachers, scientists, and medical doctors) are both deemed responsible for State waste. Social leaders and union representatives, in particular, have been designated as part of “the caste” and accused of defending their personal interests over those of workers. Arguing in this way, libertarians, like Milei, have denied that individual interests can be advanced by collective organization.

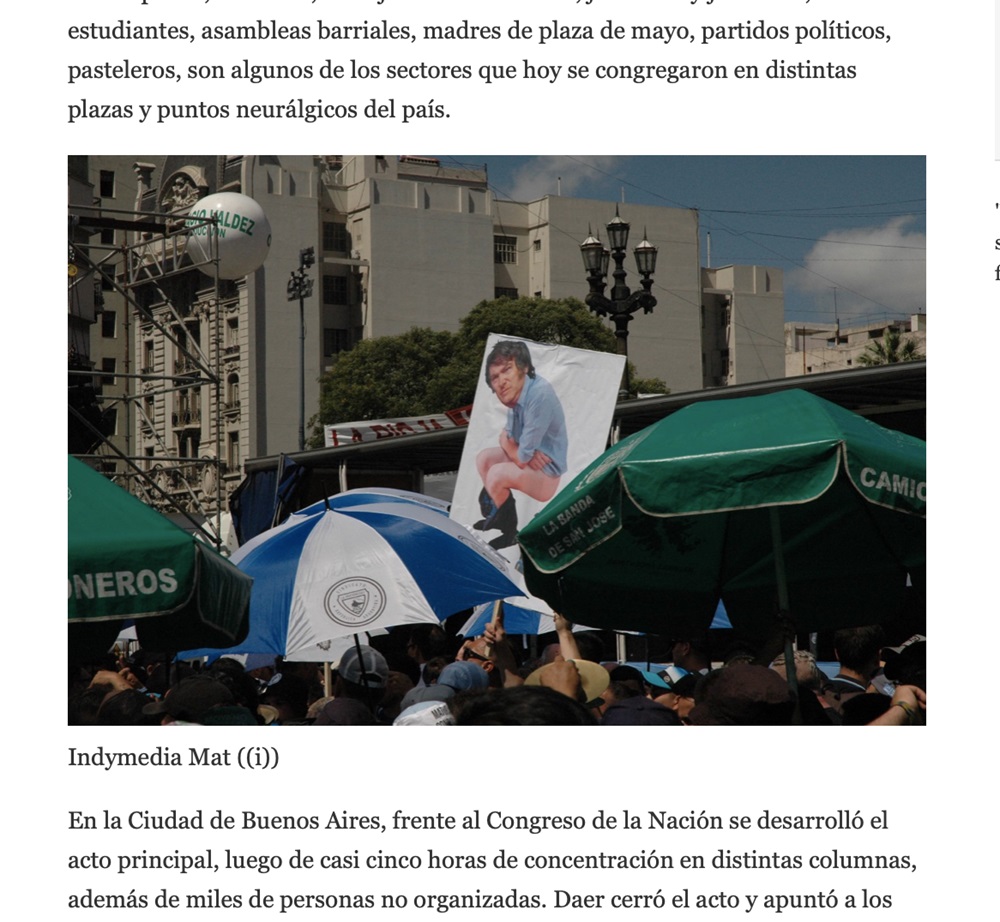

This Manichean vision of evil collectivists and angelic individualists underpins Milei’s idea of crisis. In arguing that the nation was in a “terminal crisis” because of the political and economic order of “la casta”, Milei has promised respite for suffering Argentines by radically reshaping the relationship between the “economy”, “society”, and “politics”. In presenting himself as an outsider, he capitalized on the widespread social discontent, frustrations, and disappointments of ordinary Argentines. Milei sought consent for radical liberalization schemes, and his November 2023 electoral victory appears to have validated his agenda. Judging by the electoral results, consent to these policies seems firmly rooted in working people. According to survey data, Milei gained the vote of over half of informal and formal workers and almost 64% of the self-employed. However, only 45 days after Milei took office, 1.5 million people mobilized across the country in a general strike against the liberalisation program, preceded and followed by a series of local and sectoral protests and strikes.

This scenario raises some questions: Do voting patterns in the election indicate that Argentine workers have taken a profound “right turn”? Alternatively, is Milei’s victory only a contingent rejection of the prior government at a critical conjuncture? Are post-election protests an expression of fear by “the caste” (as the government claims)? Or have workers broken with the assumption that radical marketization is the answer to their individual problems? And what lessons can we draw about working-class dynamics from prior moments of popular consent to liberalisation? In this post, I attempt to answer these questions by revisiting an earlier moment in Argentina’s history, when President Carlos Menem took office and implemented sweeping liberalisation measures.

Memories of Yesterdays: The 90s reloaded?

In many respects, the current sociopolitical scenario resembles the early 1990s, when Menem began his first term in office amid a hyperinflation crisis and launched an aggressive program of economic liberalisation. It was a time of “globalization” when the pro-market “Washington Consensus” was globally ascendent. The neoliberal road that Argentina took was part of a global attempt to stabilize a shaky geopolitical order. The program was broadly supported by Argentina’s main corporations and the entire capitalist class, which launched a broad offensive against labor rights and working conditions, backed by a narrative of “cultural change”, which mirrored official discourses about “modernization” and “being integrated into the world”. During two terms in office, Menem’s government reshaped the conditions of reproduction of Argentina’s working people, deepening their monetization and privatization, while reconfiguring the country’s labor markets.

There are significant commonalities in working people’s experience between the moment of contested “restructuring” of global capitalism in the 1980s-1990s and now. Revisiting that earlier moment can therefore help us better understand popular consent to Milei’s pro-market, right-wing policies in the present. Below, I outline these commonalities, drawing on data from fieldwork conducted in 2000-2002, 2005-2007, 2010-2012 and 2014-2018 with steelworkers (Soul 2015), their communities and their unions, as well as data from ongoing fieldwork with workers and communities linked to the agro-industrial sector.

The politics of Argentina’s neoliberal (Menem) and libertarian (Milei) governments are distinguished by their sweeping attempts to eliminate all state-backed and collectively shaped conditions that support the reproduction of working people. Upon taking power in 1989, Menem sent to Congress two bills that deregulated state education, health, and security institutions, and enabled labor flexibilization. Similarly, President Milei issued a “Decree of Necessity and Urgency” (DNU) and has sent to Congress an ambitious bill entitled “Bases and Starting Points for the Freedom of Argentines”. Together, these measures aim to enact a massive social-political reset by removing all “collectivist” and “regulationist” mechanisms, while de-regulating the economy, privatizing social provisions, and dismantling institutions that mediate market competition in areas like health services, education, sports, and cultural production. Both the Menem and Milei governments promoted far-reaching labor reforms aimed at facilitating dismissals, extending probation periods, making working hours more flexible, and expanding informal labor relations. They also intended to restrict the right to strike and union activity in the workplace, to impose individual bargaining over collective bargaining, and to cut unions’ financial resources.

In the “private” sphere, enterprises and companies during both periods entered a dynamic characterised by workplace closures, employee lay-offs and mass dismissals, new managerial strategies and technological innovations, and prominent claims about “cultural change” by managers and businessmen. Both then and now, corporate spokespersons asserted a need for radical changes. Recently, Paolo Rocca, the CEO of Techint Group, one of Argentina’s major industrial corporations, expressed support for the government’s plans for “resetting” Argentina’s economic structure, and asked other businessmen to commitment to “sacrifices” that would be needed to enhance national performance in a competitive world market. In workplaces, employers are already enforcing the bill’s provisions, overruling those stated in existing collective agreements, and thereby undermining the working conditions of new employees.

These measures, implemented amid a post-pandemic employer offensive and rising inflation, have been justified on the basis of three ideological claims, which I have also identified among steelworkers and will examine below. However, the outcome has not been unambiguous consent to these measures by ordinary workers. This is because the threats posed to their material conditions of reproduction have also motivated workers, even individuals who voted for Milei, to struggles against these measures.

Changes are “necessary and unavoidable.”

When I discussed the Menem years with anyone employed in the state-owned steel plant where I conducted my research in the 2000s and 2010s or in the surrounding community, it was surprising how persuaded they were about the necessity of restructuring. A common refrain was: “We knew it was this or nothing. Things could not continue as they were. There were no other solutions.”

In 1989, when Menem took office, annual inflation was over 3000%. In 1990, it was over 2000%. As a result, it was impossible to schedule industrial production. But it was also impossible to budget for family expenses, like food, schooling, holidays, or the purchase of household appliances. A Thatcherist belief that “there is no alternative,” which working families immersed in chaotic hyperinflation adopted, paved the way for consent to Menem’s reforms. Workers knew the offensive was coming. But they felt it was pointless to resist.

After COVID-19 restrictions ended in 2021, Argentina’s economic situation worsened. The government’s financial difficulties and escalating inflation became topics of everyday discussions. In 2023, when Milei won the election, formal employment and incomes for ordinary workers were decreasing. Most new jobs created in recent years have been informal, self-employed, or based on individual, unprotected contracts (monotributistas). The increased precariousness of ordinary Argentines has fed into a sense of suspension, instability, and “dislocation” (Polanyi 1947; Harvey and Krohn-Hansen 2018).

As in the 1990s, the popular assumption is that regressive restructuring is necessary to restore stable conditions of reproduction. Milei has turned this assumption into a government program, while endeavouring to transform the silent resignation of ordinary Argentines into active consent.

Sacrifice is necessary to recalibrate the effort-reward equation.

Both, Milei’s and Menem’s governments asked the population to “sacrifice” for the nation in order to remedy a terminal national crisis. When he took office, Milei asserted that it would take two years of sacrifice to abandon decadence and to embark on the road to prosperity. On Christmas Day 2023, the Minister of Economy posted on X a message to the population, thanking them for their sacrifice and support for austerity measures. By “sacrifice” he meant enduring the negative impact of a 118% devaluation of the Peso Argentino, the deregulation of prices for basic goods, and the cutting of food assistance to community organizations.

The notion and logic of sacrifice is at the core of many workers’ effort-reward equation: the renunciation of immediate pleasure, wellbeing, and fun will allow for future material, social and affective achievements. The concrete contents of “sacrifice” change from generation to generation, and between different labor situations. However, “rewards” remains quite the same: better living conditions, understood as owning a house, getting a car, and raising children without privations. The relationship between efforts and rewards mediated by “sacrifice” is intimately connected to a valuation logic: getting valuable things requires effort. Therefore, working people’s well-being is always related to “sacrifice”, and sacrifice is linked to hard work.

As increasing aspects of workers’ daily reproduction are monetized and privatized, neoliberal hegemony has restructured the effort-reward equation. This reinforces individualistic assessments of the effort-reward equation and devalues remaining collective practices and institutions involved in daily reproduction. Over the last years, the neoliberal effort-reward equation has been cracking due to increasing inflation, decreasing power purchase, and worsening working conditions. Therefore, many workers have experienced a sense of their own effort being under-valued, while that of “lazy and useless” people is overvalued (Kalb 2022).

Milei promised to restore the effort-reward equation after a period of “sacrifice” marked by austerity policies. Far from rejecting Milei’s appeal as unfair and manipulative, working people in Argentina see it as a call for collective sacrifice necessary to restore the real value of things and of effort. The assumption that public workers or popular economy cooperatives “steal” a share of the social product that they do not contribute to producing underpins the moral vindication of personal deprivation: “I pay what I can afford; nobody gives me anything.” The perceived need for a temporary sacrifice thus informs social acceptance of Milei’s agenda.

Order must be restored to market relations.

Menem and Milei both advocated radical social marketization as the path to a social order that promised individual fulfilment, well-being, and happiness. To this end, private property is key. The logical chain of private property – market relations – freedom was established by classic liberalism. Neoliberal and libertarian discourses have intensified this claim and its relevance for establishing social order. Consequently, Milei’s government has attempted to remove regulations on prices and on public service fees that have been crucial to working people’s reproduction. In claiming that these regulations create a social fiction that devalues peoples’ efforts, Milei argues that their removal is necessary to the restore the “natural” market order of things—that is, to restore the “true” value of individual effort.

Managerial policies have similarly promoted individualization as a way to erode collective practices that support the power of unions in workplaces. An assumption shared by workers in the 1990s and now is that their effort is devalued because of conditions that trade unions have created to protect lazy people. For example, subcontracted workers see the devaluation of their own effort as correlated to the “privileges” enjoyed by permanent workers. Consequently, in times of crisis, competition among workers (for a job, promotion, or bonus) intensifies.

The power of this logic lies in its general character: the “people” are abstract market actors who can become rich through their independent effort. The centrality given to individual initiative partly counteracts the daily sense of powerlessness and failure that working people feel when trying to achieve their goals and obtain “rewards”. The promise of success through individual effort is thus attractive not just for informal precarious workers, but also for formal workers suffering deteriorating working conditions, unfair taxes, and the devaluation of their wages.

The persuasiveness of this logic is based on the material aspects of social reproduction under capitalism. Currency devaluation and inflation not only de-structure everyday lives but are powerful mechanisms for increasing the appropriation of surplus value from working people to corporations, managers, and business owners. By presenting “free market” relations as objective and natural, neoliberals before and libertarians today can present the full deployment of “the market” as a condition for resetting conditions of reproduction, and for re-situating individuals in their appropriate social location. This entails a fabulous recoding of relations of exploitation, dispossession, and violence, and the de-legitimization of collective solutions to common problems.

Silent consent and popular unrest

In sum, I argue that recent dislocations in Argentina underpin consent for pro-market policies. On the threshold of neoliberal and libertarian governments, Argentinian working people experienced dislocations rooted in the “impersonal” and “abstract” mechanisms of inflation, stagnation, and devaluation. Hyperinflation, conceived as “monetary violence” (Bonnet 2008), paved the way for neoliberal consent, while steady stagnation, deepened by the pandemic, eroded the “market” capacities of ordinary people. Since capitalist market relations are the background of social reproduction, the crisis created serious obstacles to ordinary people’s everyday reproduction. That is why the “normalisation” of market relations – even if it entails “sacrifice” – appears to be a viable route to a fair equation of effort and reward. The individualisation that this logic promotes is understood by people as increasing their control over their lives. This logic seems to be especially persuasive for young informal workers. However, in promoting marketization, competition, and individualization as the driving forces of working people’s reproduction, the government must destroy the dense network of cooperative and collective links that underlie working people’s everyday lives.

The general strike on 24 January 2024 was the highest point of post-election popular mobilization. Since then, a series of collective actions have raised a broad array of demands over, for example, public education, social assistance, protection for community organizations, and public transport tariffs. These demands go beyond labor conditions and wage claims. They highlight working people’s desire to preserve a non-commodified sphere of reproduction, and for core democratic rights. For the time being, resistance to Milei’s policies lacks a more expansive political agenda to contest “market relations” as the core of everyday reproduction. Nonetheless, Milei cannot easily discredit the social unrest as just “the caste” defending its “privileges”. It is too soon to assume that consent for market liberalization has been eroded and that those who voted for Milei are now mostly in the streets. But at the very least, the general strike has shown that complete marketization is a contested project. Hopefully, in the days ahead, in the struggle over capitalist restructuring, working people will manage to forge their own “resetting”—one that goes beyond the market as “the natural order of things”.

Julia Soul is a researcher at CEIL – CONICET Argentina. Her current research is about crisis and transformation of the working class in Argentina and Latin America since neoliberalism. She has conducted fieldwork with steelworkers in Argentina, and México and in international unions for more than 15 years, and with agribusiness workers since 2022. She has been a member of Taller de Estudios Laborales since 2002.

References

Alberto, Bonnet (2008) La hegemonía menemista. El neoconservadurismo en la Argentina. Editorial Prometeo. CABA

Kalb, Don (2023) “Double devaluations: Class, value and the rise of the right in the Global North.” Journal of Agrarian Change, 23(1), 204–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12484

Soul, Julia (2015) SOMISEROS. Configuración y devenir de un colectivo obrero. Editorial Prohistoria. Rosario

Cite as: Soul, Julia. 2024. “Between Confrontation and Silent Discipline: Working-Class Dilemmas under Javier Milei’s Far-Right Government in Argentina” Focaalblog 8 March. https://www.focaalblog.com/2024/03/08/julia-soul-between-confrontation-and-silent-discipline-working-class-dilemmas-under-javier-mileis-far-right-government-in-argentina/