The February 2021 military coup in Myanmar put an end to the country’s ten-year period of quasi-civilian electoral rule—the so-called democratic transition, as it was optimistically called. Since then, nation-wide anti-coup protests, a violent military/police crackdown, and the emergence of a decentralised armed resistance movement have garnered extensive international and domestic media coverage. Far less attention, however, has been paid to the detrimental impact of the coup on the livelihoods of millions of ordinary Myanmar workers within the country and abroad.

It was to better understand the coup’s impact on Myanmar migrant workers that we began a collaborative research project in late 2021—specifically, on how the coup, coupled with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, has impacted Myanmar migrant domestic workers in Singapore. While a more detailed presentation of our findings awaits future academic publication, we offer here a brief account of the post-coup experiences of some of the women we interviewed between late 2021 and early 2022.

Post-coup precarity

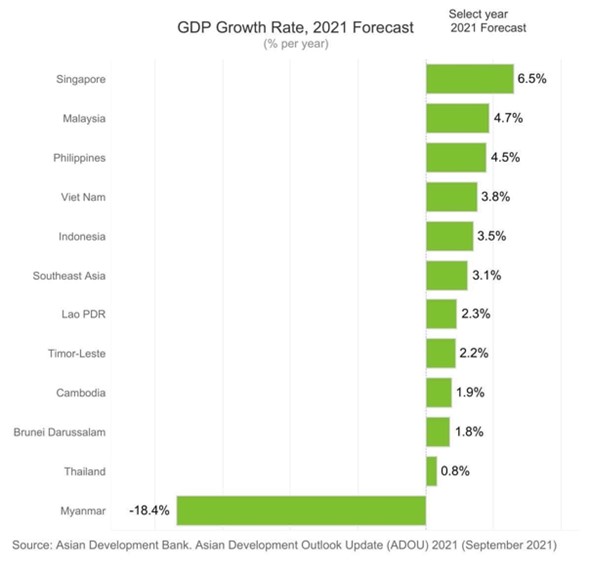

Following the coup, mass workers’ strikes and violent military/police repression prompted widespread workplace closures across public and private sectors in Myanmar. Hundreds of thousands of factory workers fled the industrial zones around Yangon for the relative safety of their home villages. And many foreign brands ceased sourcing products from Myanmar-based factories. Due to these combined factors, 250,000 garment sector jobs were lost in Myanmar by July 2021, while 1.6 million jobs were lost over 2021 as a whole, according to the International Labour Organisation. By September 2021, the Asian Development Bank projected that Myanmar’s annual GDP growth rate would be -18.4% (see Figure 1). Under these conditions, employers in Myanmar leveraged post-coup precarity to lower wages and undermine workplace organising.

Even before the coup, workers in the industrial zones around Yangon were labouring under highly precarious conditions—conditions that COVID-19-related economic contraction greatly exacerbated. Since the coup, heightened economic precarity and enduring military repression have significantly increased the number of people attempting to leave the country for work abroad. Under renewed military rule and pandemic-related travel restrictions, many individuals trying to leave the country have encountered bureaucratic delays, state-imposed barriers and unscrupulous brokers seeking to exploit the current crisis. Some aspiring migrants have sought to reach foreign countries through perilous irregular channels. Meanwhile, the 4.25 million Myanmar migrants residing abroad face added pressures to increase remittances to family back home, and to postpone plans to return permanently to Myanmar.

These restrictive conditions formed the context of our research. In what follows, we present some of the narratives of Myanmar migrant domestic workers in Singapore to show how post-coup precarity in Myanmar has negatively impacted their migration experiences abroad.

Migrant domestic workers in the post-coup moment

After ten years of labouring in Singapore, 43-year-old Ma Khaing felt she had had enough. The two-year contract she had signed at the start of 2020 was supposed to have been her last. “I had decided that I’d return to Myanmar in February of this year,” she told us in early 2022. Her plan, however, had been thwarted. First it was the COVID-19 pandemic. “When COVID started, the economy constricted a lot,” Ma Khaing explained. But also, her widowed mother contracted the virus, as did all seven of her siblings in Myanmar. “My mother had to close her betel stall… And since she closed it, I obviously had to send back more [money].” Eventually the pandemic “calmed down,” said Ma Khaing, and her mother was able to reopen her stall. “But now,” she added, “the [post-coup] unrest has happened. So, she’s had to close her stall again.” All of these developments impinged on Ma Khaing’s decision making: “I’d been planning to return—to go back home to stay when the two years [of the contract] finished. But now, because of the turmoil in Myanmar, I’m no longer going back. I’m going to continue [working in Singapore]. I’ve got to stay on, obviously.”

As a Myanmar migrant domestic worker in Singapore, Ma Khaing’s experiences were far from unique. Indeed, her life course paralleled that of tens of thousands of her compatriots who labour as domestic workers in Singapore. Of course, Myanmar migrants in Singapore faced difficulties even before the coup, and before the pandemic. Yet, with the onset of the pandemic, conditions for migrants deteriorated further.

In late 2020, the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics, a Singaporean migrant worker advocacy and support organisation, reported the following trends in migrant domestic worker employment conditions due to pandemic-related restrictions and pressures: increased workload, imposed work on rest days, heightened surveillance by employers, increased restrictions on communication and mobile phone usage, loss of employment, substantial wage decreases, increased verbal abuse by employers, and increased workplace stress due to prolonged isolation with employers.

Notwithstanding the effects of pandemic-related restrictions in Singapore, our research focused specifically on how recent developments in Myanmar have impacted migrants abroad. On this matter, the domestic workers we interviewed highlighted two main issues–both related to the worsening economic situation back home. These were: needing to send more remittances to family members and needing to remain working longer in Singapore. Thus recounted Ma Sein, a 36-year-old woman from Yangon:

“After Covid started, I had to send back more remittances, obviously. For example, I’d been sending 350 to 400 [Singaporean dollars] per month. But then I had to send over 500, or up to 600 per month because prices increased and all my family members became unemployed. When Covid started, they could have continued selling in the market, but I didn’t want them to go outside. It was better for them to stay at home.”

Ma Shwe, a 33-year-old woman who supported her three school-age siblings and whose widowed mother sold rice at a market, felt similarly pressured. “When Covid started, some businesses had to close,” she recalled. “My plan had been to just work two years in Singapore. But then Covid happened, and it wasn’t possible to return to Myanmar.”

Such were the added challenges for migrant domestic workers in Singapore during the pandemic. The 2021 military coup in Myanmar has compounded these difficulties. Alongside intensified post-coup violence and repression, the ensuing insecurity and economic fallout have reduced livelihood options in the country and have heightened pressures on family members abroad to increase their financial support. The coup and ensuing humanitarian crisis have thus exacerbated what were, under the pandemic, already difficult conditions for Myanmar migrants in Singapore.

After the coup, recounted Ma Shwe, “The economic situation [in Myanmar] got worse, of course. Some people had to pawn their belongings just to eat, because they had no work.” Responding to these conditions, many migrants increased their remittances. “I’d been sending money each month—three lakhs [S$219] for one month,” explained Ma Ni. However, “since the coup, I’ve been sending about four to five lakhs [S$292 – 365].”

Meanwhile, most migrant domestic workers in Singapore are seeking to renew their contracts, and many have set aside prior aspirations for future livelihoods in Myanmar. “I had planned to save and buy a home [in Myanmar],” recounted Ma Sein. “Now, because of the political situation and the Covid situation, my plan isn’t feasible anymore. Given the current situation, I’m going to continue staying [in Singapore]. Will I stay for one year, two years, or four or five years? I can’t say.” Ma Yadana reflected similarly: “I’d thought about opening up a restaurant [in Myanmar], or something like that. But now, I have to continue on here [in Singapore].”

Understandably, these conditions are also motivating individuals in Myanmar to seek work abroad in larger numbers. “Now, everyone wants to leave, since there isn’t work in Myanmar,” said Ma Sandar. “Especially since the coup,” she added, “there are those with passports waiting to leave for Singapore.” Confirming Ma Sandar’s observation, Mizzima News reported at the end of 2021 that the Yangon passport office had seen a near ten-fold increase in applicants despite a doubling of the passport fee.

Ruth, an employment agent we interviewed, offered further detail. “Now, since the coup, there are so many people who want to come [to Singapore],” she said. “There are many people who want to leave [Myanmar]. In the past, I’d have about 50 maid profiles to advertise. Now, I have 200 to 300. There are so many. There are so many people who want to come. There is so much supply.” The reason, Ruth explained, is that since the coup, “There’s no work anymore. There’s no office work. There’s no work for school teachers. Workplaces are closed. Factories are closed. That’s why there are so many young women who want to come [to Singapore].”

One of the more pernicious outcomes of this situation, added Ruth, is that certain agents are leveraging post-coup precarity to reduce salaries for new migrant domestic workers below the previous standard of S$480 per month. “Some agents,” she explained, “they’ve got so many helpers [waiting in Yangon]. So, they negotiate with the helper. They say, ‘You’ll have to wait here for however many more months. So, why don’t you accept 460 or 450 [Singaporean dollars]. Then you can go faster [to Singapore].’ So, maybe some of them want to go faster [and therefore accept a lower salary].” Ruth would never do this, she assured us. But “some agents,” she acknowledged, “are unethical.”

Stressing the impact of home-country conditions on migrant domestic workers in Singapore risks conveying a rather deterministic analysis. It is thus important to note, as well, that many of the women we interviewed expressed a sense of political awareness and agency, in which they saw themselves as active participants in the post-coup struggle against renewed military rule in Myanmar. Ma Sein, for example, said, “Now I send [money] to support my family. I send whatever is left to support the revolution.” Similarly, Ma Yadana explained,

“At first, I thought I’d gone abroad to work for my family. Later, beyond my own family’s financial status, I realised that it’s actually because of my country’s poor conditions that I had to migrate, and it’s not because of my family… That’s why I haven’t returned. Because even if I do have the financial means, while people around me are struggling, it can’t be like that. That’s why I can’t return just yet… Even if we win the revolution, there’s a lot of work to be done in rebuilding.”

Conclusion

The narratives of the women we interviewed reveal the intimate linkages between deteriorating home-country conditions and the financial and psychological stresses that migrants face abroad. A related analytical implication is that migrant labour regimes in countries of arrival cannot be disentangled from home-country conditions and larger geopolitical shifts. Our inquiry into migrant domestic workers’ experiences in Singapore thus advances a global-relational analysis of migrant labour arrangements.

Drawing on the personal accounts of migrant women in Singapore, we also write this piece to inform ongoing discussions of Myanmar’s post-coup landscape. The enduring effects of the pandemic, compounded by post-coup insecurity and economic contraction in Myanmar, means that more and more migrants are likely to leave the country for work abroad in the coming years. The experiences of migrants abroad are also an important aspect of current social-political dynamics within Myanmar. Whatever the outcome of the ongoing revolution in Myanmar, the current crisis will continue to significantly impact the lives of Myanmar migrants abroad in the years to come. Despite, however, the evident difficulties that Myanmar migrants face in the post-coup moment, the narratives of the women we interviewed reveal political critiques and personal aspirations expressive of the self-emancipatory agency of a nation-in-making.

Khin Thazin is a researcher in the National University of Singapore’s Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health. She has worked with local NGOs on migrant support programs and has researched migrant labour issues in Singapore. Her recent publications include, “Keeping the Streets: Myanmar’s Civil Disobedience Movement as Public Pedagogy” and “Homespace: The Intimate Precarity and Oppositional Praxis of Migrant Workers in Singapore.”

Stephen Campbell is Assistant Professor in the School of Social Sciences at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. He is the author of Border Capitalism, Disrupted: Precarity and Struggle in a Southeast Asian Industrial Zone (2018), Along the Integral Margin: Uneven Development in a Myanmar Squatter Settlement (2022), and numerous articles on labour and migration in Myanmar and Thailand.

Cite as: Thazin, Khin and Campbell, Stephen. 2022. “How the Myanmar coup has impacted migrant workers abroad.” Focaalblog, 7 June. https://www.focaalblog.com/2022/06/07/khin-thazin-and-stephen-campbell-how-the-myanmar-coup-has-impacted-migrant-workers-abroad/