This post is part of a feature on “Debating the EASA/PreAnthro Precarity Report,” moderated and edited by Stefan Voicu (CEU) and Don Kalb (University of Bergen).

Contemporary anthropological praxis sits at the intersection of two ethical traditions. Many anthropologists are equipped with both a sophisticated understanding of the ethics and politics of representation and a practical knowledge of the bureaucratic norms and standards of institutional research ethics (informed consent, confidentiality, anonymisation etc.). And yet, if the PrecAnthro/EASA report (Fotta et al 2020) and the recent scandal at the HAU journal tell us anything (Kalb 2018, Murphy 2018, Neveling 2018, Singal 2020), it is that our disciplinary ethics does little to ensure the ethical conduct of our discipline. As other contributors to this debate have noted, the situation described in the report demands a political and an anthropological response. It requires us to unionise and work ethnographically to understand “the structures of feeling and the conditions of possibility for collective mobilization” (Narotzky 2021). In my opinion, the report should also provoke us to re-evaluate the ethics of anthropological knowledge production.

I welcome the PrecAnthro report for helping to illustrate the scale of anthropological casualisation in Europe, but it is true that my feelings likely reflect how closely the report describes my own experiences of academic precarity: I was educated in the UK and since completing my PhD in 2015, have worked on fixed-term research contracts. As Susana Narotzky (2021) and Natalia Buier (2021) note, the report privileges the perspectives of researchers like me, whilst excluding the experiences of some of the most marginalised precarious workers in anthropology such as low-paid teaching staff for whom EASA membership is neither professionally advantageous nor affordable. I write here from my located perspective as a post-doc who has worked in the field of research ethics for a number of years.

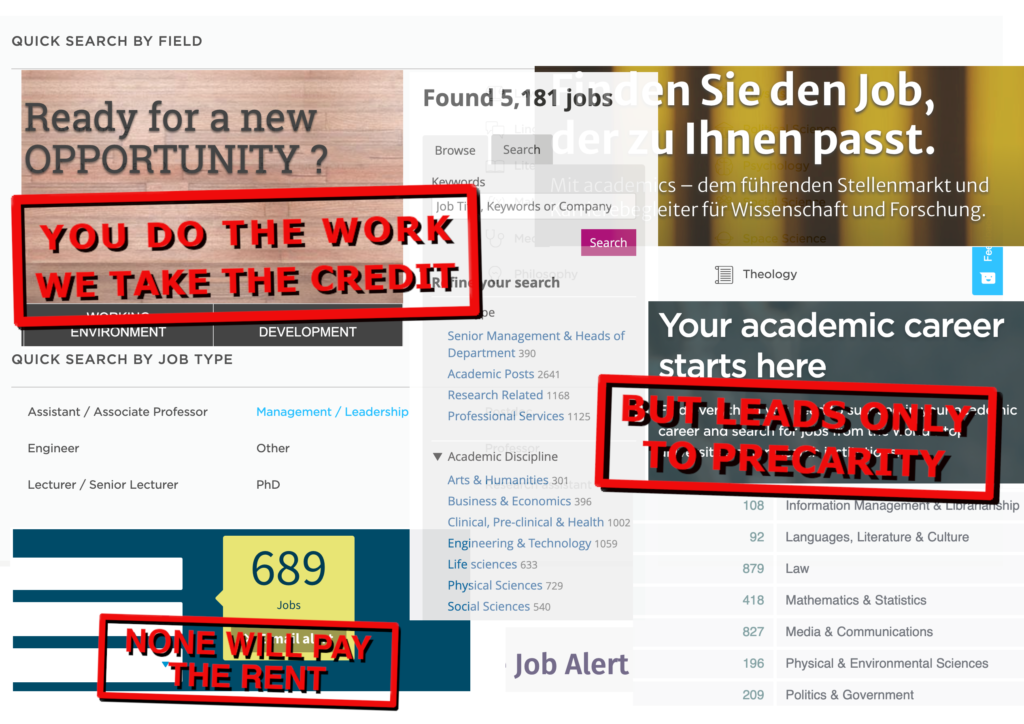

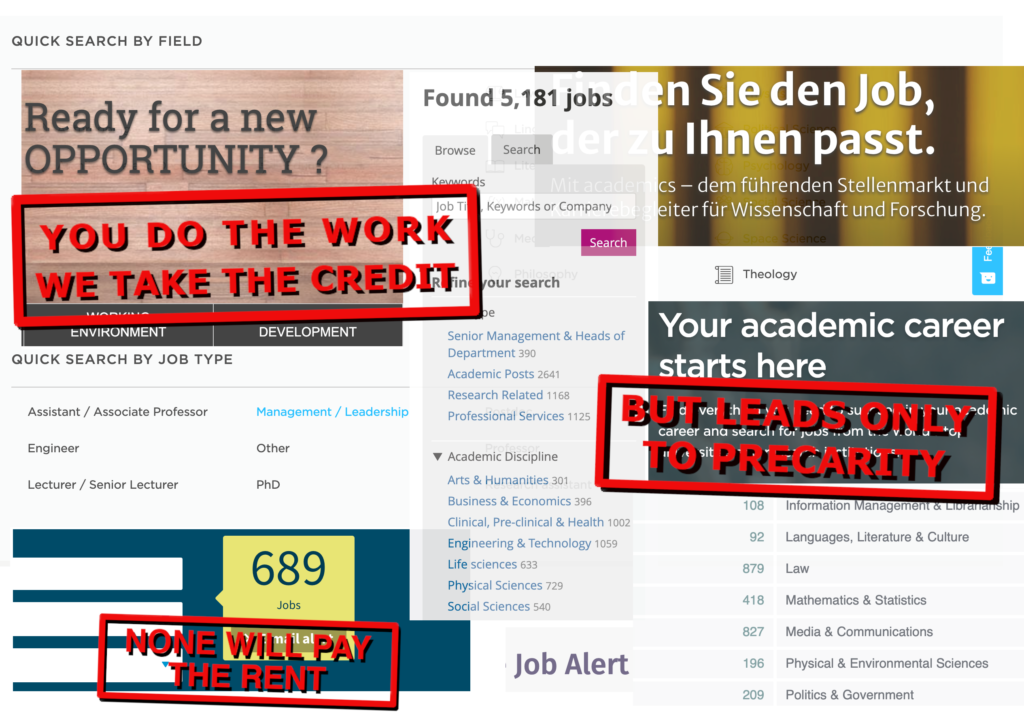

I found little to disagree with in the FocaalBlog commentaries on the PrecAnthro report and would only contend that I do not believe that anthropologists feel uncomfortable talking about precarity within our discipline. On the contrary, in fact, I think that anthropologists are more than happy to discuss academic precarity because they see it as a largely externally driven phenomenon – part of the same great process of neoliberal bureaucratisation that has devolved power from academics to university managers and driven a culture of performance review and job insecurity across the piece (so called publish-or-perish). Rather, I would think, what makes anthropologists feel uncomfortable is talking about how the precarity of junior colleagues leaves them vulnerable to exploitation by senior colleagues and reluctant to report abuse and bullying due to a fear of reputational damage (Kalb 2021, Drążkiewicz 2021, Rajaram 2021). The kind of exploitation that allegedly took place at HAU may be extreme, but as Neveling (2018) argues, it sits within “a spectrum of social, economic, and political processes that have always driven academia and continue to do so” and that reflect the general conditions of capitalism. Yet, whilst we should of course foreground the political economy of academic casualisation in order to understand the grounds for collective resistance, we must also question what it means to produce anthropology is a way that is sensitive to the risks of exploitation inherent to the contemporary academic process. Such a project would necessarily be as much about the ethics of anthropological knowledge production as the political economy of precarity.

One of the difficulties that anthropology faces here is a lack of familiarity. Our existing professional ethics and standards are attuned to the practices of conducing fieldwork and writing ethnography. We are not used to thinking about how we interact with each other as a problem of anthropological ethics. Neither do we tend to think of “the anthropologist” as someone who is particularly vulnerable. Indeed, it was not so long ago that the anthropologist was seen as quite the opposite of a precariously employed, exploited worker. Typified by the image of Stephen Tyler on the cover of Clifford and Marcus’s Writing Culture (1986), the figure of the anthropologist-as-writer marked a dawning disciplinary confrontation with the idea that ethnography was not neutral scientific description, as had apparently previously been assumed, but a genre of “persuasive fiction” largely produced by elite, white men, working under conditions of colonial and post-colonial privilege. Anthropologists, who understandably tend to privilege the ethics of their own discipline to those imposed from the outside (i.e., institutional research ethics), have become keen observers of the politics and ethics of representation. Anthropologists are skilled at unpacking assumptions and revealing the structures of inequality that determine whose experience counts and who gets to speak for whom – as demonstrated in this debate by the various incisive critiques of the limits of the PrecAnthro survey. And yet it is unclear how effective our existing disciplinary ethics alone can be when the subject of exploitation is neither a subject of investigation, nor ultimately representation, but rather a fellow anthropologist.

The PrecAnthro report evokes a strikingly different image of “the anthropologist” to that of the elite, white man of crisis of representation. The typical respondent in the report is described instead as “a woman aged around 40… educated in either the UK or Germany… possibly in a relationship but has no children… and probably dissatisfied with her current employment and her work–life balance due to the fact that she works on a fixed-term contract” (Fotta et al 2020: 1). The report further illustrates what many already knew: contemporary anthropological knowledge production relies on a precariat of low-paid anthropological workers (postgrads, postdocs, teaching assistants etc.), many of whom will never obtain a permanent contract in the discipline nor academia more generally. What does the growing visibility of this version of “the anthropologist” mean for anthropological praxis? Are we to continue to imagine that the rights and wrongs of anthropological knowledge production can be discussed independently of the labour relations that structure our discipline? If not, then we may need consider whether our existing professional ethics are equipped to deal with the moral and political realities of anthropological research in the 21st century. Indeed, if it is our ambition to build the kind of class consciousness required for collective mobilisation, then we may need to start by acting in solidarity with precariously employed anthropologists and try to envisage ways that our working practices can be used to help mitigate, rather than exploit, the forms of vulnerability that academia creates.

Adam Brisley is a post-doctoral researcher at Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona. He has a PhD from the University of Manchester and has previously held post-doctoral positions in the universities of Manchester and Bristol. His research interests focus on the relationship between care and political economy in the context of health systems crisis.

References

Buier, N. 2021. “What sample, whose voice, which Europe?” Focaal Blog, 27 January 2021. http://www.focaalblog.com/2021/01/27/natalia-buier:-what-sample,-whose-voice,-which-europe?/

Clifford, J. and Marcus, G. 1986. Writing culture: The poetics and politics of ethnography. University of California Press: Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

Drążkiewicz, Ela. 2021. “Blinded by the Light: International Precariat in Academia” Focaal Blog, 5 February 2021. http://www.focaalblog.com/2021/02/05/ela-drazkiewicz-blinded-by-the-light-international-precariat-in-academia/

Fotta, M., Ivancheva, M. and Pernes, R. 2020. The Anthropological Career in Europe: A complete report on the EASA membership survey. European Association of Social Anthropologists: https://doi.org/10.22582/easaprecanthro

Kalb, Don. 2021. “Anthropological Lives Matter, Except They Don’t” Focaal Blog, 27 January 2021. http://www.focaalblog.com/2021/01/27/don-kalb:-anthropological-lives-matter,-except-they-don’t/

Kalb, Don. 2018. “HAU not: For David Graeber and the anthropological precariate.” www.focaalblog.com/2018/06/26/don-kalb-hau-not-for-david-graeber-and-the-anthropological-precariate.

Murphy, Fiona. 2018. “When gadflies become horses: On the unlikelihood of ethical critique from the academy.” www.focaalblog.com/2018/06/28/fiona-murphy-when-gadflies-become-horses.

Narotzky, S. 2021. “A History of Precariousness in Spain” Focaal Blog, 29 January 2021. http://www.focaalblog.com/2021/01/29/susana-narotzky:-a-history-of-precariousness-in-spain/

Neveling, Patrick. 2018. “HAU and the latest stage of capitalism.” FocaalBlog, 22 June. www.focaalblog.com/2018/06/22/patrick-neveling-hau-and-the-latest-stage-of- capitalism

Rajaram, Prem Kumar. 2021. “The Moral Economy of Precarity” Focaal Blog, 9 February 2021. http://www.focaalblog.com/2021/02/09/prem-kumar-rajaram-the-moral-economy-of-precarity/

Singal, J. 2020. How One Prominent Journal Went Very Wrong: Threats, rumors, and infighting traumatized staff members and alienated contributors. They blame its editor. The Chronical of Higher Education, October 5th 2020: https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-one-prominent-journal-went-very-wrong?bclid=IwAR1F_go7fNeeRXDtTLZmAhBsNlKjv8ta3fb8e3o2uRn5WD-74cVqWKwsiVI

Cite as: Brisley, Adam. 2021. “Ethics and the Anthropological Worker.” FocaalBlog, 9 February. http://www.focaalblog.com/2021/03/24/adam-brisley-ethics-and-the-anthropological-worker/