This post is part of a feature on “Debating the EASA/PreAnthro Precarity Report,” moderated and edited by Stefan Voicu (CEU) and Don Kalb (University of Bergen).

The PrecAnthro Collective within EASA has shown staying power and bite. That is what the EASA precarity survey demonstrates (Fotta, Ivancheva and Pernes 2020). Mariya Ivancheva has turned her elected stint in the Board of the European Association of Social Anthropologists to good use. She, her co-authors, and her multiple collaborators and supporters in and outside of EASA should be applauded. This is Europe-wide anthropological collective action at work, and it goes far beyond business as usual.

The PrecAnthro Collective emerged in 2016 and is embedded in a network of international junior academics – initially with roots mainly at Central European University (then still in Budapest) and at the University of Barcelona, but spreading North and West from there, partly following the international trajectories of their members. It is this international Left-anthropology network of collaborators that has been fundamental for the bite and the staying power – for now. The Anthropology of Labor Network is another embodiment of the alliance.

The other enabling factor was obviously time. The time is right, overdue in fact. Things have been irresponsibly sliding in academia and elsewhere. We have had enough, and we sense that we are, certainly after the Covid pandemic, at a deeply contingent global moment (see also Kalb 2020). Anthropological lives do matter, even when they are just one random slice of the precaritized European middle classes. They also signal something important about the whole present structure: they show how contemporary capitalist states are treating those parts of their middle classes who express less than fully corporate and governmentalist desires. The message is clear: “you’d better think twice, you’ll be on your own”.

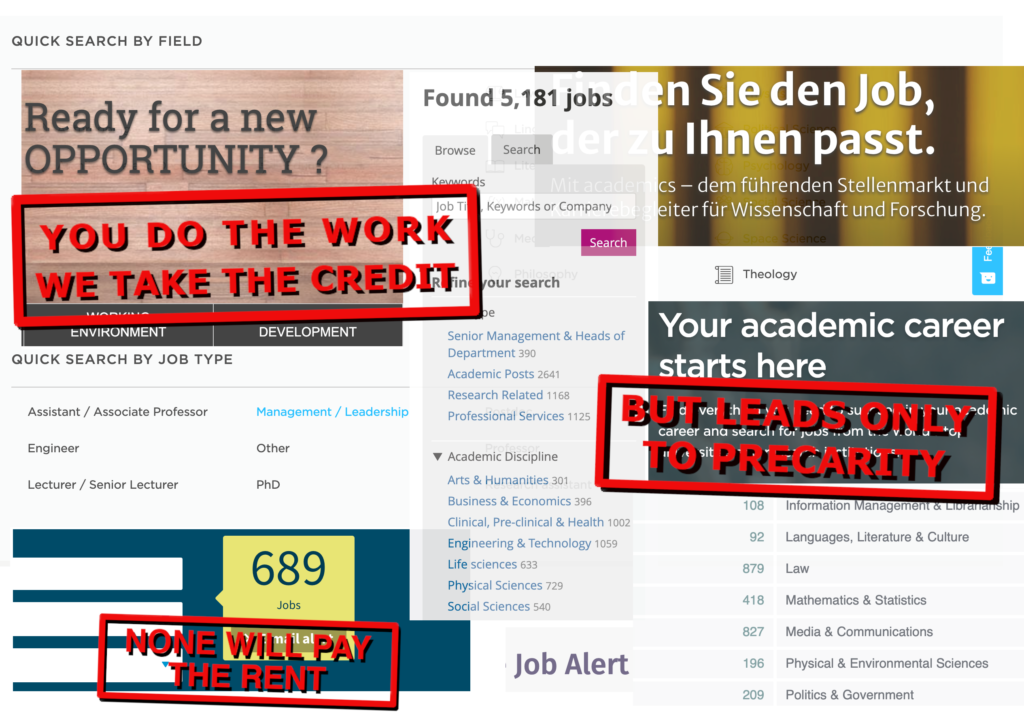

All round reparations are by now required. The whole thing is ridiculously precarious, unfair, and exploitative, and not even efficient; we are running into a capitalist wall. And we know now, with the anthropology of money, credit and finance in hand (and with a bow to Modern Monetary Theory) that it is not an issue of a lack of public money at all. It is about political will (Hann and Kalb 2020; Graeber 2011). Academia should not be run as McKinsey would like it. Our own discipline nowadays has really no other professional rationale than helping to produce democratic, intelligent, and progressive people and societies, not just “more stuff” – research articles, students, diplomas, scholars – against lowest cost. No wonder that we, as a discipline, are not doing well; no wonder that the qualitative parts of the social sciences, and of course the humanities, are not doing well. We are just being tolerated by increasingly corporate universities serving deeply capitalist societies thrown into cold blooded mutual competition and rivalry.

Precarious academic careers in which gaining tenure before 40 is sheer luck and gaining tenure after 45 is not likely – a picture that emerges from the EASA survey – are quite possibly not worth the love, the blood, and the tears. This is both despite and because of the sustained dedication that is required of, as well as extracted from, junior scholars. Dedication is joy as well as self-exploitation. With so many not getting there, squeezed out at the cut-off moment, or sacrificing so much in the process – children, relationships, ‘work-life balance’ as the survey professionally calls it – it appears as a waste of life, time, talents, training; a losing labor of love. Anthropologists and academics more broadly, Europe-wide and beyond, should collectively refuse; but the collective will and leverage clearly fails them, on all levels.

This picture is general, but with significant local variation, as should be expected in Europe. While things look bleak everywhere, not just for the anthropological precariat but for the discipline as such (not researched in this survey), the academic systems in Central Europe, the German and Italian ones, also the ones in Visegrad and Spain, shaped by states that were shaken by revolution and counter-revolution and thus afraid of politicized intellectuals, are still decidedly meaner for professional academic careers than the ones in the Northwest.

In the former regions, the survey shows, tenure even before 45 can hardly be expected. We know how junior scholars in these systems remain outrageously dependent on full professors (and the full professors on their self-exploiting courts of juniors for necessary labor ‘gifts’ and corvées). This is true for anthropology as well as for other disciplines. But anthropology is for obvious historical reasons less well established here than in the Northwestern part of the continent, and this makes things worse. This is the core of Europe, which numerically dominates EASA. Outdated academic structures and hierarchies, as well as actively managed neoliberal ones (Netherlands, UK), will have to change if the continent wants to respond creatively and progressively to the massive transformations that are coming to us. Anthropologists should actively make that case and show that they must be part of the creative dynamism.

The survey rightly highlights gender. Not primarily because of inter-gender equity issues, which are less pronounced in anthropology than in other disciplines; but because the discipline is so highly feminized. The survey describes the emergence of an internationally circulating female academic precariat of 30-45 years old, who may ultimately succeed in the discipline or who may not, but who are all painfully confronted with dilemmas about children and partners. Many of them, the survey shows, have moved between different countries more than three times in the five years preceding the survey, pursuing postdocs and fixed time researcher jobs, perpetually reorganizing their whole lives in the process.

At that point in the report, one begins to feel the nasty side of internationalization EU-style. It becomes tangible too that the PrecAnthro Collective is narrating its own story here, and perhaps prefiguring its own coming demise. The survey shows that members of the EASA still deeply appreciate the international opportunities offered by an EU-wide labor market, but what shines through too is an equally deep emerging fatigue.

There are national circuits and international circuits, with quite a spasm between them, and with quite different career logics. This is only partly mapped by the survey, which relies on the internationally active chunk of European anthropologists who are members of EASA. Might the careers in the international circuit be even more vulnerable, in broad humanist terms, than the more local ones? The survey shows, apart from the impressive degree of internationalization of the field, that about half of junior anthropological careers even among EASA members continue to be rooted in, and routed towards, local-national arenas. The reality is of course even more local since we must assume that EASA members are biased towards the international circuit. The circulating international precariat can be expected to be comparatively successful in chasing the postdocs offered by the international top scholars winning the big grants. They are trained to publish in English, satisfy high professional productivity standards, know the international circuits, and come with recommendations from other senior international scholars. This group is eminently exploitable but even more eminently expendable. The teaching tasks left vacated by the top scholars are often taken up by those with more locally embedded careers. Those local career paths encompass both research and teaching, increasingly with a bias towards the latter.

Might the more roundabout, intra-institutional, local vertical interdependencies, with their close-up relations of reliability, availability, exploitability, and obligation that naturally accumulate within local institutions over the years, remain the safer road to academic survival? I know that quite a few scholars with Europe-wide international careers often find their (final?) tenured jobs back in their ‘home’ countries. With the ongoing separation of research and teaching at underfunded universities, the most administratively pressing parts of academic production processes rely in any case more and more on pools of locally available academic teachers. In both cases, local and international, it seems, reliable intimate and domestic partners must appear as the most valuable assets in life.

The expendability of the internationalized anthropological precariat should not surprise us. Was the EU not designed to strengthen the nation state by helping to internationalize it – but not quite to overcome it? Perhaps we are also here at a certain tipping point. We need reparations all around, in all the senses of the term. That has become so obvious that a certain ‘enlightenment egalitarianism’ has even been spreading among economists and other governance experts lately. But without a federalizing EU taking political control over the potential sovereignty offered by the Euro – so robustly on display these days – how could that even become thinkable?

Don Kalb is Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Bergen, leader of the Frontlines of Value project, and Founding Editor of Focaal and Focaalblog.

Bibliography

Fotta, Martin, Mariya Ivancheva and Raluca Pernes. 2020. The anthropological career in Europe: A complete report on the EASA membership survey. European Association of Social Anthropologists. https://easaonline.org/publications/precarityrep

Graeber, David. 2011. Debt: The First 5000 Years. New York: Melville House.

Hann, Chris and Don Kalb. Eds. 2020. Financialization: Relational Approaches. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Kalb, Don. 2020. Covid, Crisis, and the Coming Contestations. http://www.focaalblog.com/2020/06/01/don-kalb-covid-crisis-and-the-coming-contestations.

Cite as: Kalb, Don. 2021. “Anthropological Lives Matter, Except They Don’t.” FocaalBlog, 27 January. http://www.focaalblog.com/2021/01/27/don-kalb:-anthropological-lives-matter,-except-they-don’t/