I confess that the first time I met David I was not impressed. It was in 2006 at a conference in Halle. David gave a 50-minute summary of what was to become his Debt book. He covered 5,000 years in 50 minutes, and this was in an era when the Grand Narrative was very much out of fashion. His presentation struck me as rambling and incoherent.

Over the past 15 years I have come to change my mind about him completely. I have just published an article (Gregory, 2021) where I have argued that Sahlins and Graeber should have been awarded the Nobel Prize for Economics. For many, this is high praise, but I can’t be sure that David would accept it. His approach to the theory of value stands opposed to everything the so-called ‘Nobel Prize’ for Economic Science symbolises.

My brief today is to discuss his book Towards and Anthropological Theory of Value (2001). I shall keep to that brief as best I can. I must say, however, it was only after reading his books on Anarchism (2004), Direct Action (2009), Debt (2011), and Bullshit Jobs (2019) that I began to get my head around the central arguments of his Value book, by far his most difficult book. What struck me about all these books was the extraordinary unity of theme and content. I see them as a five-volume study of the value question. I am not saying that this is the best way to interpret what he has done. There are many ways to approach his work. This is the one I find most useful.

In the acknowledgements to his Value book David thanks everyone at Palgrave except the editor who made him switch around his title. If we restore the order he wanted, the main title of his book becomes, The false coin of our own dream, and the subtitle, Toward an anthropological theory of value. This inversion gives us a different angle on his work. The word ‘toward’ suggests a movement, not yet completed, from an old theory to a new one. It also brings the expression ‘the false coin of our dreams’ to front and centre. The origin of this expression can be traced back to Mauss and Hubert in their General Theory of Magic (1902-03; 1972), but David gives the metaphor a 21st century twist. As I see it, the phrase false coin of our own dreams defines a paradox that is the central organizing metaphor of all five volumes of his books on value. But what does he mean by this paradox?

My short answer to this question is that he is referring to the political battle over those big ideas that can change the world. For him the value question is, first and foremost, the battle over competing images of wealth. The false coins are the images of wealth produced by the dreamers of yesterday, the false coiners of an image that has become adulterated and debased through excessive use over time. David the dreamer wants to recoin these debased images of wealth to create a new image of what could be. His dream is not a fantasy. It is a real possibility grounded in economic history, cultural geography, and the political present. Graeber the dreamer, then, is a political activist who wants to appropriate the false coins of the ruling elite, melt them down, and forge something new in collaboration with those who have a hopeful image of the future. He wants to join them in the streets as they ‘shout, clamour and make joyful noises’ in the now obsolete sense of the word ‘dream’ (OED).

What is this new image of wealth?

David, we must never forget, was born in New York and raised in Chelsea, just four miles from Wall Street. He has a New York-centric view of the world he has never lost. This visual image captures the essence of his approach as I understand it. It shows the Charging Bull sculpture that artist Arturo Di Modica secretly installed near Wall Street in 1989 in the wake of the 1987 Black Monday stock market crash. In 2017 Kristen Visbal installed her sculpture of Fearless Girl facing down the Charging Bull, but following complaints, the Fearless Girl was relocated to a different part of Wall Street, totally transforming Fearless Girl’s symbolic power. She now represents, Google Maps tells us, the fight for female equality inside the boardrooms of Wall Street. The original juxtaposition of images admits of a very different interpretation, especially when we overlay with the lyrics of the ‘blah, blah, blah’ song the rebellious young sing.

Greta’s ‘blah, blah, blah’ is a quote from a song very popular among the young. The other line of the song goes ‘Ja, Ja, Ja.’ The language of this song is not double Dutch, even though the elite might think so given that the composer, Armin van Buuren, was a Dutchman. A Dr Sev from Poland has mixed Greta’s speech and Armin’s song. It was premiered on YouTube 30 September 2021. The sonic image, created to excite the passions of the young, raises a serious question: What does ‘No more blah, blah, blah’ mean? What is the message the young are trying to convey to those in power with lyrics of this kind?

Enter David Graeber, the bilingual Wall Street ethnographer. Not only has he has learned the language of the bulls and the bears inside the offices of Wall Street, but he has also learned the language of the young protestors on the streets outside in New York, London and elsewhere. In May 2019 he attended the Extinction Rebellion in London. He duly recorded what they said and reported it (Graeber 2019). The following is my very brief gloss on how he might re-present their point of view.

‘No more blah, blah, blah’ is a polite way of saying: ‘tell us the truth about climate change. Stop lying. Stop talking bullshit. Don’t give us bullshit jobs to do. We, too, are capable of imagining different possibilities for life on earth. If you old folks in power don’t listen to our dreams, we are all finished (one imagines that the protestors may have used different F-words in this final sentence).

The distinction here between the liar and a bullshitter, which David (2018: Ch 1, fn 10) notes but does not develop, is very important one. The bullshitter, Frankfurt (1986) notes in his classic essay, is one who exaggerates or talks nonsense to bluff or impress. The liar, by contrast, deliberately sets out to mislead with falsehoods. In other words, it is one thing for an academic to talk nonsense unintentionally to impress, but quite another for a politician like Trump who knows the truth to deliberately propagate falsehoods. Bulls can also produce manure, which is to say that the academic bullshitter can produce something very useful.

We are dealing here with two quite distinct values. The ambiguous quality of academic bullshit requires that it be handled with the greatest of care and respect. David does precisely this in his writings. However, his unique meandering rhetorical style takes some getting used to. I can now see some virtues in it, but it is not one that I would urge my students to imitate!

Let me now move to David’s analysis of the language of those on the other side of the barricade. The bulls and the bears of Wall Street who excite the emotions and imagination of academics and well as sculptors, singers, and other creative artists. On the one side we have academics from the schools of business and economics who crunch the numbers and give advice, for a price, to the politicians and shareholders who run the show. On the other side, we have academics like David who occupy the streets and call for radical change, often at some cost to their careers.

Academics, then, can be divided into three categories: those who work for Wall Street, those who work against it, and those interested in other questions. It is a quaint feature of the English language that those who work for Wall Street are called ‘policy advisors’ whilst those who work against it are called ‘political activists.’ Henceforth I shall refer to both as political activists. It is obvious, then, that the schools of business and economics and law are full of political activists whilst anthropology has very few. This raises the uncomfortable question for us non-activists of the political implications of our inaction.

Activists in the schools of Economics and Business come in many different stripes and political persuasions defined by their approach to the theory of value: Neo-Smithian, Neo-Ricardian, Neo-Marxist, Neo-Keynesian and Neo-classical among many others. Most belong to the mainstream neo-classical school epitomised by the work done by the economists of the Chicago School of Economics, a school that has produced ten Nobel Prize winners, two short of Harvard, the top school.

The image of wealth that informs the thought of these people, I assert, is the false coin of David’s dream, the anti-thesis that defines his thesis. Let me be clear. When it comes to an image of wealth, there is a sense in which David is opposed to the whole history of European economic thought from Adam Smith in 1776 to the Nobel Prize winners of 2021. Everyone. Smith, Ricardo, Marx, Jevon, Keynes, Friedman. It is a different matter when it comes to concepts of value and specific theories of value and, especially those of Marx. Some fine conceptual distinctions between images, concepts and theories are at stake here. I will come back to this trichotomy below. In the meantime, it suffices to note that when a theory of value uses concepts to make an argument it presupposes an image of wealth as a moral precept.

What does this ‘false coin’ of European economic thought look like? What image of wealth does it excite in the mind of its beholders?

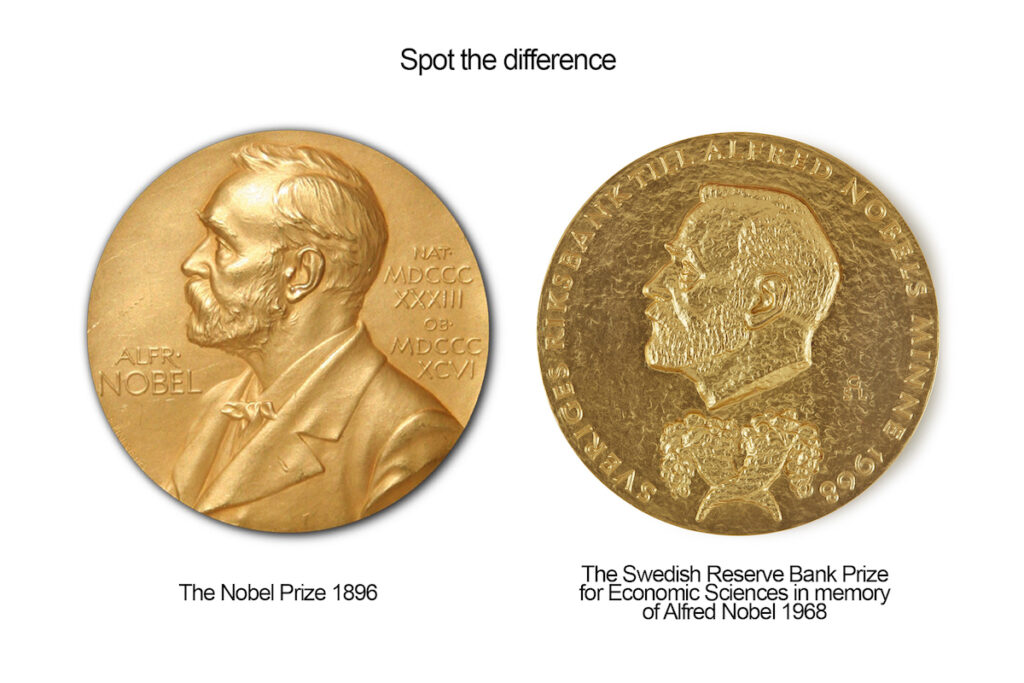

In 1895 Alfred Nobel established the Nobel Prize to be awarded to those who ‘have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.’ Five prizes are given each year: Physics, Chemistry, Medicine, Literature and Peace. In 1968 the Swedish Central Bank donated money for a prize in memory of Alfred Nobel. This award, which is administered by the Nobel Foundation, it not a Nobel Prize. However, by the operation of the Law of Contagious Magic, it is falsely called the Nobel prize in Economics when in fact its real name is the Swedish Reserve Bank [Sveriges Riksban] Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. Nobel’s descendants are very unhappy about this situation. ‘Nobel despised people who cared more about profits than society’s well-being,’ said Peter Nobel, a great grandnephew. In 2001 they demanded, without success, that the Nobel name be dropped from the Swedish Reserve Bank award because, they said, Alfred Nobel was highly sceptical of economics and as such the existence of this award was an insult to his legacy.

David Graeber and Alfred Nobel obviously shared certain assumptions about the ability of economic science to confer wealth and happiness upon humankind. I feel, therefore, that while he would reject the Swedish Bank Prize for Economic Science, he would happily accept the Nobel Prize for Peace. As Don Kalb (2014: 115) has correctly noted, David is a political activist in the Gandhian tradition rather than the Marxist-Leninist revolutionary tradition. Music, dance, and discussion are his preferred weapons, not guns.

David has a very interesting discussion of ‘dream tokens’ in his Value book, but I fault him for not including a discussion of the Swedish Bank Prize for Economic Science as a token of value. This is the true coin of the economic scientist’s dream, but the false coin of David’s dream. For David, the token is a ‘false coin’ because it epitomises an impoverished and debased Eurocentric image of wealth, one whose use-by date has long passed.

David’s life’s work has been the search of a better image. For inspiration he raided the cabinet of ethnographic curiosities, the historical archives, and of course spoke to the young. He has no new answers to old questions. His concern is to identify the constraints that economic history and cultural geography impose on our capacity to imagine new possibilities for life on earth. This enables him to pose new questions and to change the terms of debate. He has no manifesto, no commandments, just difficult questions that get to the root of the matter. He is primarily concerned to excite creative debate about issues of pressing importance for the human condition. If you are looking for simple answers to these questions you will not find them in David’s work. He is no messiah. He teaches us how to think, not what to think. He takes a few steps toward an anthropological theory of value. He has not arrived at the final destination.

The theory of value is the most hotly disputed subject in economics. If you ask ten economists to define money, for example, they will give you ten different answers. However, when it comes to the question of an image of wealth, there is remarkable agreement. This can be found in the image they have selected for themselves to distinguish their discipline. I refer to the image of the horn of plenty, the symbol of abundance and nourishment found in European mythology that appears on the Swedish Bank Prize for Economic Science but not the real Nobel Prizes. All 89 Economic Science laureates have all proudly accepted this token as a symbol of the true coin of their dreams.

David correctly notes that modern European economic thought has its origins in the secularisation of European economic theology. This image of the horn of plenty, which has its origins in a Greek myth, could not be a better illustration of his thesis.

For the economic scientist the horn of plenty conjures up images of Adam Smith, their revered founding ancestor, whose book, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) serves as the creation myth of their science. The very first line of his classic text introduces the image of wealth that his concepts and theories presuppose.

“The annual labour of every nation is the fund which originally supplies it with all the necessaries and conveniences of life which it annually consumes, and which consist always either in the immediate produce of that labour, or in what is purchased with that produce from other nations.” (Smith, 1776: 1)

What students in Economics 101 don’t learn is that Adam Smith had a labour theory of value, one that excited the thoughts of Karl Marx. Marx’s revised version of Smith’s labour theory of value was published in 1867. Like Smith, the very first line of Marx’s classic work introduces the image of wealth that his concepts and theories presuppose.

“The wealth of those societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevail presents itself as an immense accumulation of commodities.” (Marx, 1867:1)

What separates these two images of wealth was, of course, the industrial revolution. This revolution not only excited the thinking of radicals like Marx, but it also excited the thinking of more conservative thinkers such as William Stanley Jevons and two others who were independently working on a new theory of value that turned Smith’s objective labour theory of value upside down. This was a subjective marginal utility theory of the value based on the mathematical calculus of the pleasure and pain derived from the differential consumption of goods. It provided different answers to questions about wages, prices, and profit. Instead of a class-based historically grounded theory of profit as exploitation, Jevon’s theory was based on the figure of the abstract, ahistorical individual making free choices in the marketplace. In came Smith’s doctrine of laissez faire, out went his labour theory of value. This new theory of value was informed by a radically new paradoxical image of the horn of plenty. As Robbins (1932:47) put it, “wealth is not wealth because of its substantial qualities. It is wealth because it is scarce.” Thus, wealth for the conservative economist is not the material abundance produced by industrial wage labour, but the subjective scarcity as perceived by the universal consumer of consumption goods.

Marx’s political economy inspired the dreams of Lenin, Stalin, Mao, and others; Jevon’s economic science the dreams of the heretic Keynes, the true-believer Friedman, and others. At one extreme a very negative Smithian-inspired image of wealth as historically specific surplus value, at the other extreme a very positive Smithian-inspired image of wealth as universal scarcity value. The rest, as they say, was the history of the 20th century.

David concern is the quest for a 21st century image of wealth that enables us to put this Eurocentric image in its place and to imagine something that goes beyond it. David’s thinking was inspired by the comparative ethnographic literature which revealed to him the common ground of both sides of the debate between economists. Like Sahlins, he rejects the idea of universal scarcity and strives to extend Marx by looking at the ethnographic evidence on non-capitalist and pre-capitalist images in the quest for a 21st century post-capitalist image.

“Political economy”, David (2007: 47) notes, “tends to see work in capitalist societies as divided between two spheres: wage labor, for which the paradigm is always factories, and domestic labor – housework, childcare – relegated mainly to women.” Political economy gives primacy to abstract labour time on the factory floor. David wants to turn this upside down and give primacy to the creative thoughts and actions of people engaged in the process of reproducing their society and their children in a culture of their own making.

As a contribution to thinking about the value question in general, David’s work in not original. He is careful to acknowledge his debt to the many anthropologists who have inspired him, especially his teachers at Chicago: Terry Turner and Nancy Munn. He also acknowledges the work of many others whose work he has critiqued such as Marilyn Strathern and me. Since he published his book, many other anthropologists, such as Hart and Hann, have developed important new approaches to economic analysis that put human beings at the centre.

What distinguishes David’s contribution, it seems to me, is that his five-volume study of value is the most radical and the most ambitious. David’s life work—which now amounts to some fifteen books by my count—is nothing less than a whole socio-economic history and cultural geography of the human condition.

A defining characteristic of David’s approach is his interest in the economic theology as well as the political economy of wealth. He finds much economic theology in European political economy, and much political economy in non-European economic theology. He is concerned with what our image of wealth has become and with signs of hope of what it can become.

One of David’s projects, for example, was the deep cultural history of the secularisation of European economic theology, and the extent to which the secularisation was unfinished business. European political economy from Petty in 1662 to Marx in 1867, for example, is full of talk about Father Labour and Mother Earth as the creators of Wealth, but no mention of God the Son in the form of a wheat-God named baby Jesus or baby Zeus suckling their mother’s milk. This partial secularisation of the horn of plenty myth not only devalues women as mothers, but it also devalues males as sons as the supreme form of wealth. This is a truly great revolution in human thought, one whose English history the OED lexicographers have documented in painstaking detail. I know of no male-centric economic theology of wealth from the non-European world that goes this far. In 21st century India, for example, the quest for wealth in the Smithian laissez faire sense reigns supreme, but so too does the ideology of the son as a supreme form of wealth. As the census data on the sex ratio shows, this ideology is strongest in those areas of Northwest India where capitalism is the most advanced. Where I work in east-central India, by contrast, the economic theology of wealth assumes the ritual form of a rice goddess named Lakshmi, the daughter of Mother Water, not Mother Earth. The 31,000-line sacred poem priestesses sing celebrates Lakshmi as fearless daughter rather than dutiful wife. Indeed, her wedding to a wife-bashing husband leads to her demise. The story has a happy ending when wife-beating husband, and jealous co-wives realise the error of their ways. As political economy this theology is womb-centric, daughter-centric, rice-centric, and water-centric. But as David notes, comparisons like this enable us to perceive the phallo-centric, wheat-centric European images of wealth of Political Economy for what they are.

Concluding remarks

Theories of value present themselves as descriptive accounts of the world that use a limited set of concepts—such as ‘use-value’ ‘exchange-value,’ ‘reciprocity,’ and the like—to develop general theories about what is. The flip side of these descriptive accounts is a prescription of what should be. The difference between a description and the prescription are the policy conclusions needed to bring about the changes necessary to close the gap. When it comes to Political Economy and Economic Science, the prescription is a very simple image of wealth, one that has its origins in Adam Smith’s version of the Greek myth of plenty. On the one side, an historically specific image of the abundance of commodities, on the other side a universal image of scarce goods.

This Eurocentric dream, which has enabled millions of people the world over to escape from the material poverty of their forebears, has become the nightmare of us all. It has led to obscene wealth here, dire poverty there, and environmental destruction everywhere. David rightly identifies the image of wealth that informs Political Economy and Economic Science as the false coins of our dreams today. The anthropologically and historically informed concepts and theories that he develops in all his books are all concerned to reveal the debased and worn-out nature of this false coin. He wants to encourage collective thought about how to forge a new image of wealth. The concepts and theories in his Value book, his Debt book and his Bullshit Jobs book present us with alternative images of wealth from non-European, non-capitalist economies, pre-capitalist economies, and 21st century capitalist economies respectively.

The image of wealth that informs David’s dreams, like all images of wealth, is very simple and possible to achieve. He wants to move the focus of attention from the production of commodities, and the consumption of goods, to the reproduction of people, one where the children of today have a say in the world of tomorrow. The task of re-imagining a world where people can reproduce themselves has become a very urgent one. His writings reveal the huge gap between what is and what could be. His non-violent political actions, and his optimism, remind us that scholarly work is a necessary but not a sufficient means to achieve this end. Political activists in the schools of Business, Law, and Economics who give ‘policy advice’ to governments and the captains of industry have long recognised this fact. The Fearless Girl who used to oppose the Charging Bull on Wall Street reminds us that anthropology for David is not just about taking a point of view, it is also about taking action. Anthropologists, he might say echoing Marx, have only interpreted the world; the problem, however, is to change it.

Chris Gregory is an Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at the Australian National University. He specialises in the political and economic anthropology of Asia and the Pacific.

This text was presented at David Graeber LSE Tribute Seminar on ‘Value’.

References

Barnes, J. A. (1994). A Pack of Lies: Towards a Sociology of Lying. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Frankfurt, H. (2005). On Bullshit. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Graeber, D. (2001). Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of our Dreams. New York: Palgrave.

Graeber, D. (2004). Fragments of an anarchist anthropology. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Graeber, D. (2007). Possibilities: Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire. Edinburgh.

Graeber, D. (2009). Direct Action: An Ethnography. Edinburgh: AK Press.

Graeber, D. (2011). Debt: The First 5000 years. New York: Melville House Publishing.

Graeber, D. (2018). Bullshit Jobs: A Theory. London: Simon & Schuster.

Graeber, D. (2019). If Politicians Can’t Face Climate Change, Extinction Rebellion Will: A new movement is demanding solutions. They may just be in time to save the planet. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/01/opinion/extinction-rebellion-climate-change.html

Gregory, C. (2021). On the Spirit of the Gift that is Stone Age Economics. Annals of the Fondazione Luigi Einaudi, LV (1), 11-34. doi: DOI: 10.26331/1131

Hubert, H., & Mauss, M. (1902-1903). Esquisse d’une théorie générale de la magie. L’Année sociologique, 7, 1-146.

Kalb, D. (2014). Mavericks: Harvey, Graeber, and the reunification of anarchism and Marxism in world anthropology. Focaal: Journal of Global and Historical Anthropology (69), 113-134. doi:https://doi.org/10.3167/fcl.2014.690108

Marx, K. (1867). Capital. Vol. I: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production: Moscow: Progress.

Mauss, M. (1972). A General Theory of Magic, with a foreword by D. F. Pocock (R. Brain, Trans.). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Robbins, L. (1932). An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science. London: Macmillan.

Smith, A. (1776). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. London: Everyman’s Library, 1970.

Cite as: Gregory, Chris. 2021. “What is the false coin of our own dreams?” FocaalBlog, 9 December. https://www.focaalblog.com/2021/12/09/chris-gregory-what-is-the-false-coin-of-our-own-dreams.