By taking control of 22 Israeli military bases and localities, sequestering over 200 hostages, and killing more than 1,000 civilians and soldiers (although many details remain ambiguous), Hamas accomplished militarily on October 7, 2023 what no other Palestinian faction has ever accomplished. Early on during the operation, Hamas declared that its goal was to liberate the 5,200 Palestinian prisoners in Israeli prisons by means of a hostage exchange;[1] meaning that the uprising was a spectacular show of force by which to negotiate on better terms with the enemy. In this crux between military success and negotiated exchange, Hamas burst open old-new debates regarding the role of armed struggle in Palestinian movements. The predictable Israeli response is the currently unfolding psychotic war of revenge and accompanying propaganda campaign. As of the time of writing, there are some 20,000 dead Palestinians, tens of thousands more injured, over a million displaced, critical infrastructure irreversibly damaged, one of the oldest cities in the world all but razed to the ground, and 3,000 newly arrested prisoners. More horror likely awaits in the very near future. Was the uprising worth all the death and destruction? Will any good come out of this? Away from the media frenzy of political talking heads and party pundits, these are the kinds of questions that have emerged on the streets of Ramallah, Jerusalem, Amman, and elsewhere, where misery and despair fuse headily with pride and possibility. Misery and despair, that is, because a genocide of Palestinians not only in Gaza but also Jerusalem and the West Bank seems frighteningly plausible; and pride and possibility because for some it has become conceivable for the first time—unlikely perhaps, but somehow still conceivable—that Israel can be defeated militarily.

The nature of Palestinian resistance has had historical ebbs and flows (see Qumsiyeh 2011). Tracing Palestinian uprisings from their first instances in the 1920s (four decades after the establishment of the first Zionist settlements) to October 7, one can observe clearly identifiable Zeitgeists, from periods of political petitioning, times of boycotts and other grassroots satyagraha, other times kamikaze attacks, and seasons of war. In recent decades, the pax americana that was supposed to have been the Oslo Accords ushered in an era of liberal politics in the 1990s (see Haddad 2018, Rabie 2021), which then exploded into the Second Intifada in the early 2000s. After this, the nature of Palestinian movements changed; fragmented, the Palestine Liberation Organization[2] placated by an end-of-history worldlessness,and a Palestinian public was left disenchanted with the failure of liberal politics but without knowing where else to turn. Hamas, during this period, became the unlikely vanguard of Palestinian resistance; a national liberation movement without the nation mentioned anywhere in its name.[3]

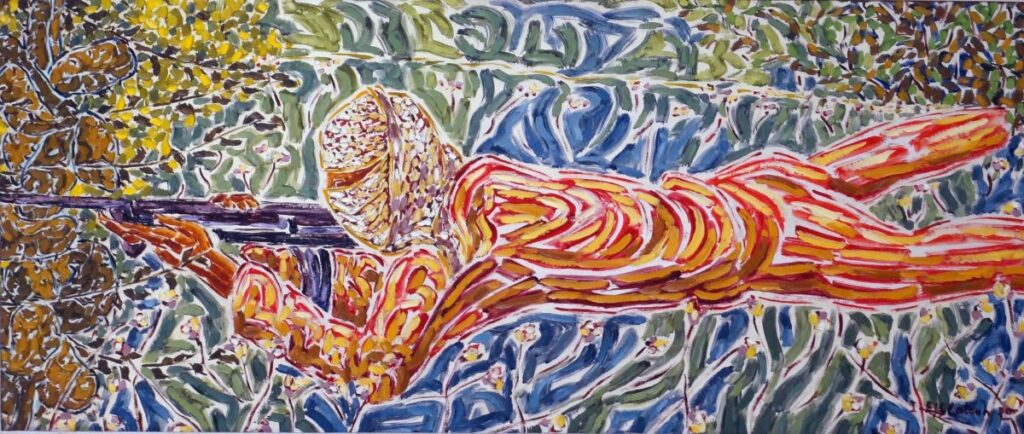

In contextualizing the place of armed resistance in the current chapter of the Palestinian story, I present below translations of three short texts by Bassel al-Araj (1984-2017), a Palestinian pharmacist by day and blogger by night who was assassinated in his apartment by Israeli forces in 2017. Al-Araj left behind a body of writing, often blog posts, that has greatly inspired the current generation of leftist Palestinian activists. Al-Araj advocated that the intellectual in Palestine not be a passive commentator but actively “engaged” in resistance, and he coined the term al-muthaqaf al-mushtabak “engaged intellectual;” a nod to the New Man of Guevara-esque romance, in a play of words that is more poetic in Arabic than in English. Some erroneously confuse the epithet with the even more irresistible al-muthaqaf al-musalah “armed intellectual,” a slip that Al-Araj would not have protested. His agitating against the security coordination between the Palestinian Authority and Israel landed him in a Palestinian prison in 2016. He was released following a hunger strike. Six months later, he was killed by Israel. He was thirty-three years old.

The following pieces are translations from Arabic taken from a collection of Al-Araj’s writings, letters, and Facebook posts, published by the Beirut-based leftist publisher Bisan in 2018. In the first piece, written after the 2014 Israeli campaign in Gaza, Al-Araj offers a very original analysis in the aftermath of this event, observing that Hamas’s strategy of armed struggle does not break from the overall arc of armed struggle in Palestinian history. Al-Araj insists that Hamas’s strategy in the conflict was not to defeat Israel militarily, but to arrive at better conditions for negotiations. In the second piece, Al-Araj examines the gains and losses of the Second Intifada, challenging the position that the lesson from Israel’s brutal quelling of the uprising is that such uprisings are not to be repeated. Rather, Al-Araj speculates on what lessons can be learned from the intifada’s defeat so as to be able to succeed in a future iteration. In the third piece, more literary in flavor, he asks whether Palestine, as a national-territorial concept, is worth all the blood that is shed in its name. In this brief communique, he employs a revolutionary-poetic minimalism reminiscent of leftist writers of the twentieth century like, for instance, Eduardo Galeano.

Reading Al-Araj in the context of the current bloodshed, hopelessness, and despair, we might ask again: Was the uprising worth all the death and destruction? Whatever the answer may be, Al-Araj invites us to recognize the complexity of this question, and to remain faithful to rational analysis even in times of an unbearable irrationality of being.

1.

Yezid Sayigh says in his book on the Palestine Liberation Organization that the Fatah movement never took the military conflict seriously, and never viewed the armed struggle as an end in itself or the only path to liberation. Rather, the armed struggle was a means by which to negotiate a diplomatic solution.

I believe that Hamas’s experience in Gaza follows the same approach. Their political leadership views armed struggle exactly as Arafat [4] viewed it.

This is an essential difference between Hezbollah’s experience, for example, and our experience. It is also the difference between the Algerian, Chechen, Vietnamese, and Cuban experiences, and our experience.

In these other experiences, they believed that they could defeat the great powers that were their enemies. We came to the conviction that it was impossible to defeat Israel, and we never believed that returning to Palestine would involve changing the reality on the ground, but rather by appeasing the capitals of influence in the world.

2.

On the allegation: “The Intifada ruined us” [5]

2013/26/09

At the end of the 1920s and the beginning of the 1930s, the Black Hand uprising began in Palestine. It was completely crushed and its participants were eliminated within 4 months. They were either martyred, imprisoned, or exiled. During the same period, the Communist Party attempted to launch an uprising in Vietnam, which was also suppressed and the Communist Party was almost extinguished.

The important thing is that these two uprisings were two of the most excellent uprisings that humanity has ever seen: The Black Hand uprising, which was one of the most important factors leading to the 1936 Revolt [6], and the Communist Party uprising, which was one of the most important factor leading to the Vietnamese rebellion against France. The leaders learned from their mistakes, dealt with them, and corrected them.

People at that time did not renounce the option of armed struggle, nor did they brood over the colonial discourse regarding the usefulness or uselessness of armed struggle. Rather, they reviewed their experience, analyzed it, and launched subsequent uprisings that avoided the same mistakes. In contrast, Palestinians brood over the destruction the Second Intifada brought, and are reluctant to engage in any future uprising for fear of the same results.

I do not know whether Palestinians have sat down to evaluate the results of the Second Intifada in a scientific manner, especially the results of the Intifada’s military experience. Usually, when you hear a person talk about the destruction, the tragedies, the losses, and the setbacks, he is reproducing Zionist propaganda, but in his own language. This propaganda is constituted by multiple mechanisms and begins altering the Palestinian discursive space in a way that does not end only with the official line of the Palestinian Authority (the line of Mahmoud Abbas). The war against us has still not ceased, nor has the symbolic violence and hidden oppression that are the real masters of the situation. Usually when any experiment fails, the criticism focuses on the execution of the experiment, and not on the theory or ideology behind it. The results were not what we could have imagined. Was Gaza not completely emptied of settlers? And is Gaza not reaching a stage of fortification and hybrid warfare as a result of the Second Intifada? Were Tel Aviv and Jerusalem not hit hard by the early iterations of rockets that resembled cans of bug spray? Were settlements in the West Bank (in Jenin and Nablus) not dismantled because the occupation was no longer able to protect them and could no longer afford the cost of their continued existence? Did the Intifada not cost the enemy billions of shekels? And do we not realize what the Intifada did to delay the tragedy awaiting our people? Personally, I believe that the Intifada temporarily delayed a new expulsion process that was being prepared.

Evaluating the military experience of the Intifada, it appears that the armed experience of the Intifada was not actually the reason for its setbacks. Rather, there are other factors that led to this. The leadership was not able to deal with the responsibility of organizing society and preparing it for a sustained popular war. Some also had a naive understanding of armed struggle, and they flattened its essence to the extent that it did not affect the surface tensions. Recall the expression: “Carry a rifle and shoot, who will stop you?”

In addition to a lack of consciousness, as well as a lack of psychological and social readiness, there was no proper organization of the fighting forces. This led to incompetent leadership after the elimination of the first rank. As this social base was completely absent, there emerged a rift between the masses and those carrying out military action.

In addition to this, there was the counterrevolution against Yasser Arafat, and secret contacts and treasonous agreements were made under the table with the enemy. There was also an absence of preparations, equipment, strategy and combat tactics. The objective was the Oslo Accords (the homeland reduced to Gaza and the West Bank). And let us not forget here the Palestinian Authority’s dependence on the occupation for its financial, employment, and administrative system. Finally, there was a lack of conviction by some that armed struggle can change the reality on the ground. Rather, they were convinced of its use in improving the terms of negotiation, and nothing more.

In conclusion, the first thing that colonialism does is establish what is possible and impossible for oppressed peoples. Some elements of the oppressed people usually assist in this. This is done through direct and indirect brainwashing techniques, so do not trust this discourse that is transmitted and planted into our minds. Judge instead the testimonies of our people based on trusting logic and the power of liberation.

3.

Is Palestine beautiful?

I am frequently asked this question. As easy as the question seems, it is one of the most difficult questions. It is more difficult than the question “How are you?” It is difficult to answer once you realize that the real meaning of the question is: “Is this narrow coastal strip worth all this blood?” We all know that beauty is relative and that one’s environment shapes one’s aesthetic sensibilities, and that this differs from person to person. Here you have to resort to comparison to arrive at an easy answer.

But Palestine, in my opinion, is actually the most beautiful place; not because of her greenness, blueness, yellowness, redness, crops, bounty, or nature. Her beauty is that she is the one who answered my search for meaning, and she is the one who answered my existential questions, and who justifies my existence and cures my chronic anxieties.

Endnotes

[1] This number has risen to approximately 8,000 after mass arrests made by Israel since October 7.

[2] The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), founded in 1964, was for much of its history a revolutionary guerrilla movement that eventually became Israel’s political partners with the Oslo Accords of 1993.

[3] Hamas, in Arabic, is a kind of acronym for harakat al-muqawama al-islamiyya “Movement of Islamic Resistance,” but hamas also means “excitement.”

[4] Yasser Arafat (1929-2004) was the co-founder of the Palestine Liberation Organization, and was a guerrilla-turned-politician. He signed the Oslo Accords with Israel in 1993 and became President of the Palestinian Authority.

[5] Al-Araj is referring here to the Second Intifada, the Palestinian uprising against Israel that lasted roughly between 2000-2005. Its outcome, on the one hand, was the evacuation of Israeli settlements from Gaza, but also the loss of thousands of lives and the expansion of the Israeli security infrastructure.

[6] The Great Arab Revolt in 1936 was the first large-scale Palestinian mobilization against British rule and the Zionist settlement project in Palestine.

The author would like to thank Abeer Juan for assistance in the translations.

Arpan Roy is an anthropologist researching in Palestine and currently based in Berlin. His book Relative Strangers: Romani Kinship and Palestinian Difference will be published by University of Toronto Press in 2024.

References

Al-Araj, Bassel. 2018. Wajadt Ajwabti. Beirut: Bisan.

Haddad, Toufic. 2018. Palestine Ltd.: Neoliberalism and Nationalism in the Occupied Territory. London: Bloomsbury.

Qumsiyeh, Mazin. 2011. Popular Resistance in Palestine: A History of Hope and Empowerment. London: Pluto Press.

Rabie, Kareem. 2021. Palestine Is Throwing a Party and the Whole World Is Invited: Capital and State Building in the West Bank. Durham. Duke University Press.

Cite as: Roy, Arpan 2023 “Is this Narrow Coastal Strip Worth All this Blood? Bassel Al-Araj on Armed Struggle in Palestine” Focaalblog 12 December. https://www.focaalblog.com/2023/12/12/arpan-roy-is-this-narrow-coastal-strip-worth-all-this-blood-bassel-al-araj-on-armed-struggle-in-palestine/