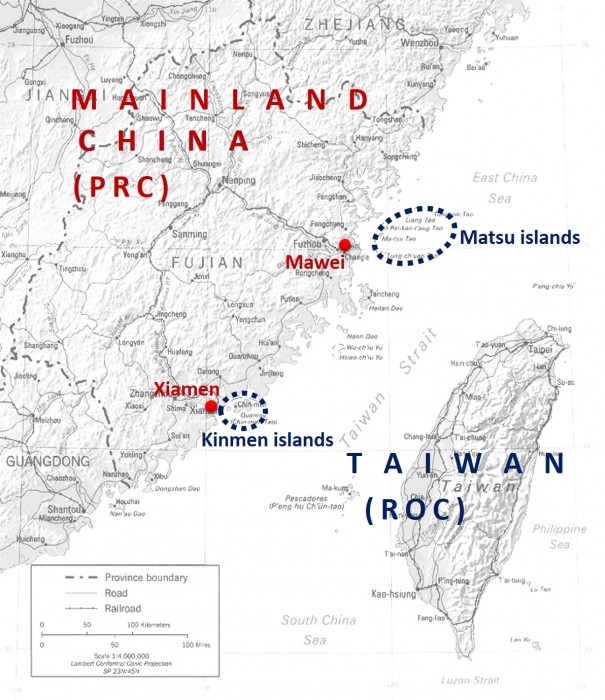

Across the globe, the Cold War abruptly delineated new borders and defined friends and enemies. Yet, there are few regions in which this was as pronounced as in the Taiwan Strait, where several groups of islands, commonly called Kinmen and Matsu (or Kinma, as abbreviated here), are located in close proximity to the southeastern coast of mainland China yet have been controlled by Taiwan since the final days of the Chinese civil war (see Figure 1). From then onward, the lives and times of the inhabitants of Kinma were destined to be forever different. This post explores through the lens of bordering how the changing strategic role of Kinma throughout the Cold War and since has defined not only the lives of islanders but also the performance of Taiwan’s state sovereignty and national identities. This brings to light that Kinma was central to the nation/state’s self-representation in “border-ordering” and to the configuration of citizen-subjects in “border-othering” and that both processes have been catalysts for a reconfiguration of the Taiwanese nation/state from the 1980s onward.

The Cold War bordering of Kinma

In the fall of 1949, Kinma islands somewhat accidentally emerged as the frontline defenses of the Republic of China (ROC) against the newly established People’s Republic of China (PRC). As the defeated Nationalists withdrew their forces from the mainland to Taiwan, their soldiers reassembled and reinforced on Kinma islands for the Battle of Guningtou. At the end of October 1949, this battle put a surprising end to the Communists’ ceaseless victories, and Taiwan has held on to Kinma ever since.

Yet, this victory was not enough for Chiang Kai-shek to regain the trust and support of the United States. Instead, the US played a role of double-dealer as they sought a way to establish formal diplomatic relations with the Communists in mainland China and cultivated and strengthened the connections with potential competitors against Chiang Kai-shek in Taiwan. If anything, the outbreak of the Korean War secured US support for Chiang Kai-shek (H.-t. Lin 2016), and the US Navy’s Seventh Fleet was sent into the Taiwan Strait to prevent an invasion of Mao’s troops. If this secured the existence of the Republic of China, the Kinma islands were now an outpost of Taiwan within visible range of enemy forces.

This changed the fate of Kinma islanders, most of them anglers, dramatically. The waterways that had been their fishing grounds were turned into front lines, and to prevent enemy infiltration the once vivid contacts with the mainland—from family visits to fishery trade and fishing boat maintenance services—were banned. All materials that might be used to make water transport vehicles, even a basketball, were ceased by the Taiwanese state (Szonyi 2008), so Kinma’s inhabitants now lived in fishing villages without fishery (Tsao 2017).

If rules, regulations, and militarization consolidated the external border on Kinma, the government also filtered and controlled the islanders’ contacts with fellow citizens in Taiwan. Without special permissions, traveling and trading between Kinma and Taiwan were prohibited. A War Zone Administration (WZA) was set up in 1954, and now Kinmen and Matsu came under military rule. The WZA took control of internal and external bordering and issued a special currency that circulated exclusively in Kinma, which facilitated control over strategic materials and rationing of daily commodities such as foodstuffs. A paramount task of the WZA was to transform the islands into “combat villages” (Y.-H. Li 1998). Regular military training was compulsory for men and women. The military made all islanders, no matter young or old, conduct military exercises to enhance their self-defense capabilities. The islanders had to build networks of trenches, tunnels, and dugouts around the villages, while Taiwan increased the number of troops in Kinma massively. At one point, 150,000 soldiers were stationed on the islands—a quarter of Taiwan’s armed forces and three times the ordinary population of Kinma (LCG 2014; Szonyi 2008). Thus, the conversion of Kinmen and Matsu into “Frontline Islands” sought to fortify not only an external border against the mainland, but also the creation of an internal border that made Kinmen an exception to Taiwan.

However, Chiang Kai-shek’s intention to defeat the Communists and retake the mainland by force was impossible to achieve. Instead, the US geopolitical containment policy included a strategy for the Asia-Pacific region that would insert Taiwan—as well as South Korea—into the emerging geoeconomic networks of US and Japanese firms. This was the driving force behind Taiwan’s economic miracle in the late 1960s (Woo-Cumings 2002), which saw the nation at the front line of a “new international division of labor” and shifted the political mandate of the government from militarization to economic development.

In the same period, the legitimacy of the ROC was seriously undermined when in 1971 the PRC won the recognition of the United Nations as the only legitimate representative of China and the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek were expelled humiliatingly. The PRC’s decisive victory in international diplomacy somewhat eased the military conflicts. New strategies of avoidance meant that the daily artillery bombardments of Kinmen continued, but now based on a remarkable informal arrangement with shells containing not explosives but propaganda leaflets and, hence, creating fewer casualties (KCG 1992). Yet, the fact that the number of troops stationed in Kinma reached an all-time high in the 1970s also raises the question of why Taiwan chose to expand garrisons at a time of de-escalation.

So far, Michael Szonyi (2008) has argued that Chiang Kai-shek increased the number of garrisons in Kinma so that the US could no longer ignore the frontline character of Kinma and would now have to include this in ongoing negotiations over the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty. Yet, this focus on geopolitical reasoning ignores the performative aspect of Kinma double borders. On the one hand, the external border maintained the Taiwanese state’s claim to be the sole representative of China, while, on the other hand, the exceptionalism of Kinma relieved all other citizens of Taiwan from taking action to retake China by force. This came in handy as it supported government efforts during the 1970s to squeeze Taiwan’s workers into the new international division of labor, because the performance of a permanent external threat in Kinma served to legitimize the ongoing state of emergency and governing under martial law in Taiwan, which eliminated political opposition during the period of “White Terror” and restricted all trade union activities that could have opposed the exploitation and accumulation of global capital in Taiwan’s factories. Therefore, we argue, Kinma constitutes an essential aspect of the resettled ROC throughout the entire post-1949 period, even though it has always been (mis)represented as a peripheral region.

The bordering of the peripheral subject

If the above has underlined how the nation/state represents itself through the process of “border-ordering,” we now turn to show how the nation/state is configured in the process of “border-othering.” In the shadow of the Cold War, Kinma islands were bordered not only to filter out the enemy, but also to identify the fellow national. On the one hand, the external border disconnected former neighbors and turned them into imagined enemies. On the other hand, the internal border connected distant strangers and turned them into an imagined community.

Yet, the most terrifying threats may come from invisible enemies, and in the Cold War setting of Taiwan, anyone could have been an infiltrator. Maintaining the border thus required constant scrutiny. For Kinma islanders, bordering practices came to dominate social relations and daily practices, which gave rise to a “peripheral subjectivity” that reflected, reified, and subverted everyday life (W.-P. Lin 2009) and served as adaptive strategies on these Cold War islands.

In the late 1980s, this would have seemed to change decisively. An indigenization movement in Taiwan sought to recognize the ROC as representative of the reimagined community of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu (TPKM), rather than that of China as a whole. While this should have ended the peripheral status of Kinma islands, it had the opposite effect. The indigenized ROC no longer needed the internal border as a constitutive performance of national unification, and with a shift in economic policies and an end to the White Terror, there was no longer a requirement for the state of exception that helped force the population into a labor force for global production networks. Even though Kinma people had been fighting for the abolition of WZA for decades, many of them felt bewildered and annoyed when Taiwan declared the demilitarization of Kinma and the withdrawal of most garrisons (Kinmen Daily News 2008).

Additionally, the external border between the Kinma islands and the mainland became porous. With the onset of economic reforms on the mainland, smuggling flourished in the border regions, and in the 1990s, most residents in Kinmen were involved in the purchase or sale of contraband from the mainland (Hsi and Weng 2003). In other words, Kinma people “illegally” reconciled with the mainlanders.

However, even in the beginning of the twenty-first century, while it was generally believed that the Cold War was over, those who tried to make cross-border contacts in Kinma islands were still threatened with prosecution—not only for smuggling but also for treason. It was in this antagonistic atmosphere that the Matsu-Mawei Agreement was controversially signed between intermediate agents backed by the two local governments of Matsu on the Taiwanese side and Mawei, a nearby harbor belonging to mainland China, on 28 January 2001. While this was a strong statement from Kinma’s inhabitants against the criminalization of border trade, Taiwan’s central government rejected the agreement flat out at first. The then Deputy Minister of the Mainland Affairs Council Ming-Tong Chen traveled to Kinmen immediately to quash the cross-border agreements (C.-S. Li 2001) and the then Chair of the Mainland Affairs Council Tsai Ing-wen (the current president of Taiwan since 2016) denounced all local officials involved for infringing the regulation on cross-strait relations and threatened punishment and prosecution. Again, this historical incident brings to light contradictions that can be developed further to analyze the border-ordering and border-othering policies of the Taiwanese nation/state.

In fact, the escalation around the Matsu-Mawei Agreement reveals the obscured disputes arising from the dynamics of internal/external rebordering. On the one hand, the decriminalization of cross-strait trade seemed to internalize the external border: the boundary between friend and enemy became obscured. On the other hand, the demilitarization of Kinma, while claiming to promote reconciliation, was, in fact, an externalization of the former civil war demarcation line towards the now sovereign border of the ROC. While the democratization and indigenization policies of the 1980s meant that now the ROC in Taiwan had no choice but to identify this border as external in order to maintain legitimacy in representing the rebordered TPKM community, the PRC maintained a definition of the same border as part of its One-China policy (according to which the ROC does not exist).

While the “illegal” signing of the cross-border agreement marks the climax of the controversy, it also opened up the possibilities of reinterpreting, rearticulating, and reassembling scalar and territorial rationalities beyond the Cold War logics. The population of Kinma desired inclusion in the actually existing, indigenized, and rebordered ROC and sought to redefine the TPKM by highlighting the historically specific close ties of Kinmen and Matsu with the mainland. If the Kinma-mainland border was defined as internal, as China wished, and if Taiwan regarded this as an exception to its otherwise sovereign state, then the stagnant relations between Taiwan and China could be moved forward. In other words, the recognition of Kinma’s exceptionality lifted Taiwan’s predicament as it allowed border trade negotiations with the mainland under the conflicting One-China paradigm without risking national sovereignty. Chair of the Mainland Affairs Council Tsai soon grasped this opportunity and soft-pedaled the incident by announcing that “it was the procedure of signing the agreement to be criticized” and that otherwise “the government recognizes the special living environment of Kinma people. We may not necessarily oppose the contents of the Matsu-Mawei Agreement” (CNS 2002). Thus, the matter was inconspicuously shifted to a procedural issue and the border was now negotiable.

This, in fact, had far-reaching implications. It facilitated the continuation and extension of Taiwan’s policy of positioning itself as a pioneer in leading global capital into China as it allowed both sides to agree to disagree. The border between Kinma and the mainland was at the same time internal, recognized by the mainland, and external, recognized by Taiwan, and in this regard, the exceptionality of Kinma was a blueprint for negotiating the legalization of border trade. In the years after the Matsu-Manwei Agreement, a series of agreements on border regulation was signed.

Double border as method

Rather than assuming borders as steady physical or institutional instruments, we have illuminated above the state-configuring and nation-building effects of bordering processes. Through the analytical lens of bordering, we see how transformations of state sovereignty and national identity are triggered and realized. While the nation/state represents itself through the process of “border-ordering,” the citizen subjects are configured in the process of “border-othering.” In this regard, Kinma has always constituted an essential part of the resettled ROC. Over the decades, the islands have been the locus where the ordering of double borders is produced and reproduced within the scalar tensions of geopolitical economy, while daily practices of internal/external border crossings reconfigure senses of otherness, which in turn catalyze the renegotiations and techniques of border control. Kinma’s debordering (legalized border trade), for example, was achieved by means of rebordering its exceptional status and thus materialized the reimagined TPKM community. It is contended here that this move not only accommodated the imaginative desires of Kinma’s inhabitants, but also repositioned Taiwan’s place-in-the-world in such a way that it enabled the nation to seize the opportunity of conquering the new frontier of capitalism opening up in a globalizing China.

Our argument is thus to consider the ordering and othering of borders not as the opposing perspectives and political projects but rather as dimensions a singular process. Studying differently scaled rationalities of development as they intersect at the border may thus offer useful analytical insights for disentangling the center-periphery relations of Cold War and post–Cold War nation/states.

Ling-I Chu is a PhD candidate in the Institute of Building and Planning at National Taiwan University. His research focuses on the spatial transformation of state and nation, as well as on the coupling/decoupling between them, and how innovative spatial strategies, such as multiple border control, overlapping sovereignty, and transborder citizenship, engender the recognition of nation/state.

Jinn-Yuh Hsu is Distinguished Professor of Geography at National Taiwan University. He is an economic geographer specialized in high-technology industries and regional development in late-industrializing countries. His research focuses on the inconstant geographies of capitalism, particularly the sociospatial restructuring of technological change and globalization processes, such as zoning state, policy learning, and mobility.

References

CNS (China News Service). 2002. “Taiwan authorities to intervene in the ‘Two Ma’ agreement signed by Mawei and Matsu [馬尾與馬祖簽署”兩馬”簽協 台灣當局要干涉].” 24 September. http://www.chinanews.com/2002-09-24/26/226143.html.

Hsi, Dai-Lin, and Weng, Tsung-Yao. 2003. “A study of smuggling in Kinmen [金門地區走私偷渡問題之研究].” Police Science Quarterly 34 (2): 241–268

KCG (Kinmen County Government). 1992. The Chronicle of Kinmen County. Kinmen, Taiwan: KCG.

Kinmen Daily News. 2008. “The impact and damage faced by the withdrawal of garrisons in Kinma [金馬撤軍所面臨的衝擊與傷害].” 26 June.

Li, Chin-Sheng. 2001. “Chen Ming-Tong warned Kinmen not to follow up, for the ‘Two Ma’ agreement has violated the regulation [兩馬協議違反現行法令 陳明通盼金門勿跟進].” China Times, 31 January.

Li, Yuan-Hung. 1998. “Militarized space control: The War Zone Administration in Matsu [軍事化的空間控制: 戰地政務時期馬祖地區之個案].” Master’s thesis, National Taiwan University.

LCG (Lienchiang County Government). 2014. The Cronicle of Lienchiang County. Lienchiang, Taiwan: LCG.

Lin, Hsiao-ting. 2016. Accidental state: Chiang Kai-shek, the United States, and the making of Taiwan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lin, Wei-Pin. 2009. “Recenteralization of the peripheral islands: A study on Matsu’s pilgrimage activities [邊陲島嶼再中心化:馬祖進香的探討).” Bulletin of the Department of Anthropology 71: 71–91. https://doi.org/10.6152/jaa.2009.12.0004.

Szonyi, Michael. 2008. Cold War island: Quemoy on the front line. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Tsao, Ya-Ping. 2017. “Fishing is so hard! Matsu fishery and fishermen’s family under the War Zone Administration [捕魚好苦阿!戰地政務體制下的馬祖漁業及漁民家庭處境).” Master’s thesis, Shi Hsin University.

Woo-Cumings, Meredith Jung-En. 2002. “National security and the rise of the developmental state in South Korea and Taiwan.” In Behind East Asian Growth, ed. Harry Rowen, 333–352. London: Routledge.

Cite as: Chu, Ling-I, and Jinn-Yuh Hsu. 2018. “Cold War islands and the rebordering of the nation/state: Kinma in the Taiwan Strait.” FocaalBlog, 18 June. www.focaalblog.com/2018/06/18/cold-war-islands-and-the-rebordering-of-the-nationstate-kinma-in-the-taiwan-strait.