Richard H. Robbins, SUNY Plattsburgh

One feature of both the economic recession of 2007/2008 and the present Covid-19-induced economic collapse is increased central bank bouts of quantitative easing. The U.S. Federal Reserve, after pumping about $500 billion in the economy in 2008 is adding $2.3 trillion as of April 2020, while the European Central Bank (ECB) launched a €750 billion asset purchase program in March. And the IMF estimates that global fiscal support to counter the economic effects of the pandemic is $9 trillion. The question is who gets it and what does it tell us about today’s political economy and what happens next (see also on this blog: Don Kalb 2020a)?

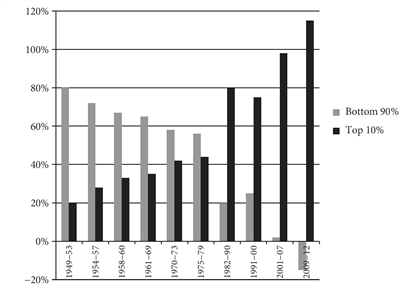

Pavlina R Tcherneva examined economic recoveries in the United States going back to 1949 and in every case over the past 60 years the top 10 percent appropriated a continually larger share of the increase. After the 2008 collapse, they confiscated 115 percent of it (see Figure 1).

Tchernava attributes this trend to central bank policies that privilege investment-led over job-led growth that, as she (2014: 49) puts it,

“…favors the capital share of income over the labor share, and … improves incomes of high-wage/high-skill workers first and low-wage/ low-skill workers last, ultimately failing to trickle all the way down to the bottom, in the form of income from jobs for the poorest of the poor.”

How does this work? At its simplest, central banks inject money into the economy by buying debt and making loans, assuming also that money that goes to member banks will be multiplied through a theoretical ten percent reserve thus turning every $1 billion injected into the economy as debt into $10 billion invested. And while central banks claim such injections benefit the whole economy, much of the money injected after 2008 into the economy gets (re)invested or used by corporations for stock buybacks, explaining why the velocity of money (a measure of how often it is spent) has remarkably declined in the U.S. and in the Eurozone.

Since most so-called stimulus money consists of loans as opposed to grants, it must further increase the debt loads of countries, regions, cities and towns, while providing a windfall for investors, provided, of course, the debts can be repaid. This raises two questions: first, what can we expect to happen with the economy post-Covid, and, second, what does this portend for state/finance relations?

The simple answer to the first question is that, if past post-collapse recoveries are any guide, we can expect unequal income and wealth distribution to increase at even faster rates with federal and local governments slashing expenses and imposing austerity and so-called structural adjustment measures on a massive scale.

The problem is that the pandemic is not the only thing on the global agenda. There is also the increased alarm at the growth of economic inequality and, more specifically, the global movement to address racism and somehow make amends for past colonial and racist policies. Any movement to address popular demands on these issues will require more money and more, not less, state spending particularly in the area of job creation and wage increases. In other words, the post-Covid world is setting up for a classic battle between capital (i.e. investors) and everyone else. What can we expect?

Optimistically we might expect democratic governments to respond to overwhelming popular demands and raise taxes on the wealthy while cracking down on tax avoidance or even imposing a global wealth tax, as Thomas Piketty (2014) proposed, as well as abandoning the neoliberal policies of the past 50 years. There really is no shortage of proposals to fix things (see e.g. Atkinson 2015). But who or what is going to do it?

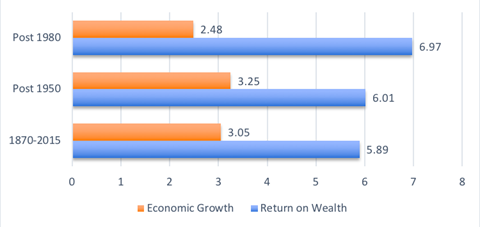

I would argue that the nation-state has been completely captured by finance and that globally we are afflicted by what I’ve called the tyranny of the rate of return. I would also suggest that we can view the history of the past 400 years as the gradual takeover of the state by investors seeking to maximize or maintain the rate of return on capital in the face of continuing threats, not the least of which is declining economic growth (see also Robbins 2020; Kalb 2020b). The problem is that over the past 150 years, as Piketty (2014), noted, the rate of return has exceeded economic growth, a discrepancy that has continually increased (see Figure 2).

Finance adjusted to the decline of economic growth by progressively commandeering the powers of the state to remove threats to the rate of return by extracting a greater share of the national income. This take-over has been a gradual process that goes back at least to the establishment of joint stock companies, the creation of the limited liability corporation, the provision in the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution that assigned personhood to corporations and the gradual abandonment of anti-trust laws. More recently, state policies to remove threats to the rate of return have been core parts of the neoliberal agenda, the most significant of which include controlling inflation, lowering taxes on corporations and investors, limiting wage increases, reducing regulations on business, privatization of state assets, eliminating or not enforcing anti-trust measures, and ensuring sovereign and private debt repayment. Policies in each of these areas reduce investment risk while penalizing everyone else (for details see here). The result is that the top 1 percent of the income distribution hold almost 56 percent of all investment instruments, the next 9 percent another 35 percent, leaving less than 10 percent for the bottom 90 percent (see Wolff 2012, 2013, 2017).

The takeover of the state by finance should not come as any surprise. Once the state assigned the right to create money to private corporations with the establishment of the Bank of England in 1694, states became debtors whose financial interests became consonant with investors (Robbins 2020, Kalb 2020b). In essence, the same factors that now permit investors to impose discipline on emerging economies to repay their debts and avoid default, are applied to wealthier countries.

John Roos (2019), asks the key question with the title of his new book, Why Not Default? The Political Economy of Sovereign Debt. It was not uncommon in the past, he says, for countries to default on their sovereign debt, primarily because there were always “small and atomized retail investors,” as he described them, who would step in to purchase sovereign debt on attractive terms. But, what he calls an “international creditor cartel” along with the concentration of finance in the hands of fewer creditors enables a more unified front to enforce payment these days. In addition, the existence of international lenders of last resort can keep debtors solvent while freeing up resources to service foreign debt. And domestic elites, with a vested interest in their country’s credit and currency, now serve a bridging role that imposes internal discipline on the state’s economic behavior (2019: 11).

Investors, he says, also have instrumental power such as lobbying, campaign financing, and the occupation of government offices. But in addition they have what he calls “structural power,” the ability “to withhold something on which another depends,” that is the “power to punish by not doing; the power to discipline through refusal,” in this case the power to withhold funds. The source of this power, he says, “resides in the capacity to withhold something on which everyone else—states, firms, and households alike—depends for their reproduction, namely credit (2019: 59).

Given all of this, and the extent to which finance has supplanted the state, the answer to the question about the economy after Covid-19 is that it will be whatever finance says it will be. And if the past is any guide to the future, investors will be paid back before money is spent on anything else, let alone on past social injustice. Given the need to rebuild or maintain basic functions such as education, communication, public health, infrastructure, and anything else required, directly or indirectly, for the maintenance of the rate of return, it is difficult to conceive of any money being available for the common good, let alone money to rectify past abuses. The next question, then, is what means of resistance exists for those wanting or demanding greater economic equality, social justice or environmental restoration?

In a democracy, citizens can theoretically communicate to their respective states through the ballot box, or, failing that, through street protests, or, ultimately, violent revolution. But how can citizens address something as ephemeral as “finance”? In his work on the movement of global capital, Jeffery Winters (1996) notes that if capital controllers, who are unelected, unappointed, and unaccountable, were all to wear yellow suits and meet weekly in huge halls to decide where, when, and how much of their capital to invest, there would be little mystery in their power. But, of course, they do not They make private decisions on where, when, and how to distribute their investments. Furthermore, under this system of private property, capital controllers are free to do whatever they wish with their capital: they can invest it, they can sit on it, or they can destroy it. States are virtually helpless to insist that private capital be used for anything other than what capital controllers want to do with it. And what they want to do with it is make more.

When in 2019 the culture jamming group The Yes Men, pranked Blackrock Investment Group by sending a letter to their clients that Blackrock would no longer invest in companies not in accord with the Paris Climate Accord, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink responded in his annual letter that BlackRock’s duty is to realize the highest rate of return for customers, regardless of the environmental consequences: “Our firm is built to protect and grow the value of our clients assets,” Fink wrote:

“…In many cases, I or other senior managers might agree with that same cause – or we might strongly disagree – but our personal views on environmental or social issues don’t matter here. Our decisions are driven solely by our fiduciary duty to our clients.”

In the past, the solution to talking to capital was through labor. The threat to withhold labor was enough to bring capital to the negotiating table. But given the decline of the power of labor and the increasing financialization of the economy that strategy is no longer feasible. Laborers are now valued largely for the debt they are forced to accumulate because of their stagnating wages (e.g. see here).

I would argue that there is only a single power that can challenge finance: the power of debt itself. As Jerome Roos (2019: 59) notes, the structural power of finance is not a one-way street. While creditors can and do withhold the credit that governments and citizens require for their existence, debtors can withhold the debt repayments and income stream on which finance depends. My colleague Tim DiMuzio and I outline the logic and the justifications for using debt as a way to negotiate with finance in our book Debt as Power. Given the monetary power of finance—upwards of $350 trillion in investment assets—and the willingness of wealth managers and investors to wield it at the expense of everyone else, it seems time for activists to marshal the power of the debt strike just as laborers used the power of worker strikes to gain a seat at the global political table.

Richard H. Robbins is Distinguished Teaching Professor in the Department of Anthropology, SUNY Plattsburgh. His books include (with Di Muzio) Debt as Power (Manchester University Press, 2016) and An Anthropology of Money (Routledge, 2017).

References

Atkinson, Anthony B. 2015. Inequality: What Can Be Done? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

DiMuzio, Tim and Richard H. Robbins. 2016. Debt as Power. Manchester University Press

Jordà, Òscar, Katharina Knoll, Dmitry Kuvshinov, Moritz Schularick, Alan M. Taylor. 2017a. “The Rate of Return on Everything, 1870–2015”, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Working Paper 2017-25. https://doi.org/10.24148/wp2017-25

Kalb, D. 2020a. “Covid, Crisis, and the Coming Contestations”, FocaalBlog, June 1st, http://www.focaalblog.com/2020/06/01/don-kalb-covid-crisis-and-the-coming-contestations/

Kalb, Don. 2020b. “Introduction: Transitions to What? On the Social Relations of Financialization in Anthropology and History”. In: Chris Hann, Don Kalb (eds.). Financialization: Relational Approaches. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books: 11-64.

Robbins, Richard. 2020. “Financialization, Plutocracy and the Debtor’s Economy: Consequences and Limits”. In: Chris Hann, Don Kalb (eds.). Financialization: Relational Approaches. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books: 65-92.

Roos, Jerome. 2019. Why Not Default? The Political Economy of Sovereign Debt. Princeton University Press

Tcherneva, P.R. (2014) “Reorienting Fiscal Policy: A Bottom-up Approach,” Journal of Post-Keynesian Economics, Vol. 37.

Winters, Jeffery A. 1996. Power in Motion: Capital Mobility and the Indonesian State. Ithaca: Cornell University Press

Wolff, Edward N. 2012. “The Asset Price Meltdown and the Wealth of the Middle Class.” Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w18559.

Wolff, Edward N. 2013. “The asset price meltdown and the wealth of the middle class.” Journal of Economic Issues, 47: 333–342.

Wolff, Edward N. 2017 Household Wealth Trends in the United States, 1962 to 2016: Has Middle Class Wealth Recovered? Working Paper, 24085. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w24085

Cite as: Robbins, Richard H. 2020. “The Economy After Covid-19.” FocaalBlog, 13 July. http://www.focaalblog.com/2020/07/13/richard-h-robbins-the-economy-after-covid-19/