Editorial note: This text was submitted by a colleague who wishes to remain anonymous; he has informed us that “this version of Viktor’s tale has been embellished in accordance with conventions of the genre (but also beyond them); at the same time, experts have ascertained that this version is not to be confused with the “fake news” that became so widespread in this era; all personal names and place names have been verified; they are real and authentic.”

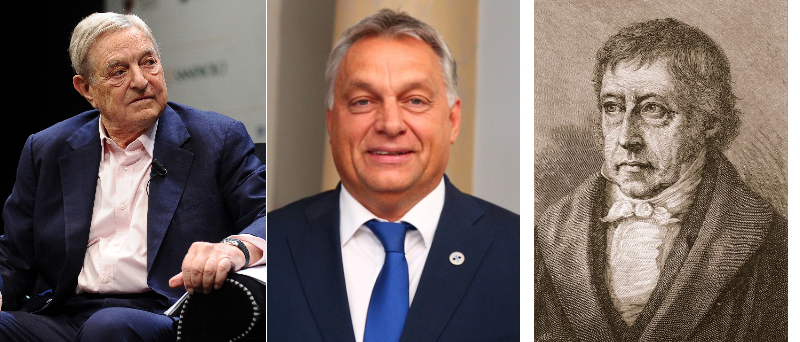

Viktor, the two Georges, and the quest for the magic formula

Once upon a time, when the Kingdom was ruled by an evil power in the east, a boy was born in the ancient town of Székesfehérvár. He grew up in the village of Felcsút. His parents, who were neither rich nor poor, expected great deeds of the lad they called Viktor. He did not disappoint, being strong and virile on the sports field and attentive in the classroom. His talents were recognized, and Viktor won a scholarship to study in the capital.

The capital of the Kingdom was a different world from Felcsút. At about this time, the great power in the east had a new leader called Mikhail, who promised great changes. Many clever people in the capital had been waiting for this moment. But Viktor did not feel at home among these sophisticates. They were as remote from his lifeworld as the apparatchiks who had toed the line of the foreign power and inconvenienced his own family in earlier decades. Viktor perceived that his people had need of something different. In a dream, he saw that it was his destiny to found a political movement dedicated to the salvation of the Kingdom. As the political climate relaxed thanks to Mikhail, Viktor gave repeated proof of his fiery rhetorical talent.

Just then, a wizard appeared on the scene. Uncle George was a native of the Kingdom who had spent most of his life in exile in the west. He too recognized this moment of opportunity, as the eastern power waned. Extremely wealthy, Uncle George hit on the idea that, to overcome legacies of isolation and oppression, the brightest young people of the Kingdom (and of another larger Kingdom to the north) should be given a chance to study in the best colleges of the west, in order to learn the key to good governance. And so, Viktor was awarded another scholarship, this time by Uncle George, and went off to a university called Oxford to acquire the secret knowledge that could not be learned at home.

In Oxford, the young Viktor was put in the charge of wise Uncle Zbigniew, who was a native of the northern Kingdom that had also come under the dominance of the great power in the east. In his exile years, Zbigniew had become an authority on the most distinguished philosopher of recent centuries on the whole continent, whose first name happened to be Georg. The ideas of this Georg seemed to bear a certain resemblance to those of Uncle George (who increasingly thought of himself as a social philosopher and not merely a philanthropist). Both Georges invoked the same magical phrase, civil society, which was somehow opposed to the state. Later, it became clear that their incantations were very different. For Uncle George, the wealthy native of the Kingdom, the unleashing of civil society was to be the remedy to decades of eastern totalitarian oppression. NGOs would be the harbingers of universal peace and democracy, in which the ultimate sovereign would be the freethinking individual—in other words, a person like himself. The classical texts of Georg were totally different. Expressed in a most peculiar tongue, it seemed that, for this celebrated philosopher, state and civil society had to be thoroughly fused to enable a unique collective Geist to fulfill its historical mission.

The dreaming spires of Oxford University (photograph by anataman via Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0).

Truth be told, young Viktor was not really very interested in either of these philosophies and their many nuances. He recognized civil society from underground publications in the capital, but he did not really understand. In Oxford, he spent little time in the libraries recommended by Uncle Zbigniew. It was more important to be constantly available on the telephone as his friends continued with the serious business of organizing their political party. When the timetable for free elections was announced, Viktor cut short his stay among the dreaming spires to return to his Kingdom. The “system change” that followed has been well documented in the chronicles. Viktor and his young party, liberal even to the point of anarchy, seemed to exemplify a free civil society in the sense of Uncle George. During these years, Uncle George himself established a new university in the capital so that in the future, brilliant young people like Viktor would not need to leave the Kingdom for their studies. Eight years after the first free elections, Viktor became prime minister (albeit following some curious maneuvers that did not quite square with the liberal vision of his benefactor).

Despite many worthy actions, such as guiding the Kingdom into a new millennium with an emphatic reassertion of the national identity, Viktor lost the next election. No one was more surprised than our hero himself. Thereafter, as undisputed leader of the opposition, the middle-aged Viktor rediscovered his rhetorical skills and remembered that magical formula: civil society. But which version of the formula was correct? Perhaps the spells of the wizard George were responsible for the increasing chaos and instability of the Kingdom. Viktor wished now that he had heeded the advice of Uncle Zbigniew and tried harder to imbibe the message of the great philosopher Georg, who for all his obscurity at least had a healthy consciousness of the destiny of his people in history. This, rather than Uncle George’s vision of an open and cosmopolitan republic of individuals, was the basis on which Viktor’s party now deepened its associational life. After another eight years, the incongruity of the people’s party constituting the opposition was resolved. Despised rivals such as Ferenc, whose thirst for power was as great as his own, and Gábor, the handsome philanderer who had been mayor of the capital for so long, were humiliated. Viktor returned to power with a clear mandate to transcend the messy pluralism that had characterized the political landscape of the Kingdom for twenty years. His pithy phrase for the new era was “illiberal democracy.”

Viktor’s great deeds for the Kingdom and his efforts to remain victorious

Throughout the opposition years, Viktor had no doubts about his own charismatic contribution to the national salvation. When the people finally assumed power, he was able to change many institutions, including the constitution itself. But even Viktor could not rewrite the rules completely. He retained his two-thirds parliamentary majority at the next elections, but was perturbed to lose nearly half a million votes. Viktor realized the need to up the ante. It was no longer sufficient to blame the Kingdom’s ills on legacies of the great power in the east and the mind-sets of their pathetic descendants. Besides, that empire was now led by the congenial Vladimir, with whom close cooperation was proving useful. More plausible enemies had to be identified elsewhere. Viktor showed supreme political skill in taking advantage of an international “migration crisis” to crystallize the destiny of the Kingdom as a unity of state and national society, embodied in his person. In his brilliant vision, this national Geist would sustain and carry forward the traditional values not only of the Kingdom but of all the peoples of the continent.

New demonic figures were found not only in the form of “others” from the east, bearers of a different faith, but also in various locations in the west itself. In the city where once the great philosopher Georg had composed his puzzling texts, there reigned a witch called Angela, who was now recklessly riding roughshod over the preferences of her own voters as well as international law. In another western city, a tired wizard called Jean-Claude presided over a technocratic dictatorship that was repressing all the peoples of the continent. Viktor was obliged to visit Jean-Claude regularly, because this city was the administrative center of the empire to which the Kingdom now belonged, but these visits and his meetings with other western leaders reminded Viktor of the disconcerting emotions he had experienced when he first set out for the capital of his Kingdom from Felcsút. Farther west again, in an imaginary non-place, there resided the wizard George, now clearly identifiable as an ogre, the ultimate embodiment of the rootless cosmopolitanism that, Viktor now understood, in both eastern and western variants, had all along been the real enemy of his people.

The dreaming spires of the Budapest Parliament (photograph by Dirk Beyer via Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 3.0).

The temperature of our hero’s ferocious campaigns against the wizard George and his devious “plan” to destroy the Kingdom (and indeed the civilization of the whole continent) was increased again in the run-up to the next elections. For months, the experts all predicted that Viktor would triumph, that the ogre would be slain forever, along with all of the subversive bodies he had financed, including his university. At first, Viktor himself was confident. He had toured the Kingdom many times, allowing wrinkled old ladies to kiss his hand and reminding hard-nosed young mayors that, just as they depended on him for the resources they needed, so in due course he would need their help to mobilize voters. He had built many wonderful stadiums, notably in Felcsút. His family members and close allies (not least the mayor of Felcsút) controlled large swathes of Hungarian industry and commerce, as well as the media. Viktor had skillfully constructed an internet image that associated him with the great folk heroes of the Kingdom in past centuries. His preelection jubilee gestures and gift hampers to the poor had never been more generous. He had called the bluff of foreign bankers who, despite his additional tax levy, had not taken their business elsewhere. Moreover, Viktor had maintained his core alliances with the neighboring “Visegrád” Kingdoms, and he knew that he could count on many supporters (such as wise old Uncle Horst) even in the western heartlands of the new empire.

Yet, deep down inside, Viktor (by now well into his fifties and heavier than he had been in his soccer-playing days) began to harbor doubts. Might the nationwide poster campaign to pillory the wizard George have been a little too crude? Had too many citizens laughed aloud when he had publicly offered to repay the scholarship he himself had received from Uncle George nearly 30 years before? Might the reduction in the unemployment rate under his government be outweighed in the minds of voters by the fact that hundreds of thousands toiled in workfare, or had left the Kingdom for the west in search of a living wage? In any case, Viktor’s speechmaking in the early phases of the election campaign was lackluster. Even on 15 March, the national holiday, he seemed more concerned to complain about defections within his own movement than to offer anything concrete for the future.

More concretely, Viktor worried that the fragmented opposition parties might contrive to unite behind a single candidate in enough constituencies to deprive him of his two thirds parliamentary majority. Defeat for his candidate in a mayoral by-election on the eve of the general election of spring 2018 came as a shock. This conspiracy against the people came to pass on the second Sunday of the fasting period, not in a stronghold of the degenerate sophisticates of the capital city but in a provincial town called Hódmezővásarhely, hitherto an archetype of Viktor’s vision of civil society. Popular discontent with something that his enemies called “corruption” (but that he saw as the noble cause of establishing a national class of sturdy yeomen-entrepreneurs to counter the domination of the transnational corporations) ensured that the candidate of the people’s party was defeated by an independent. Was the aging Viktor no longer the legitimate apotheosis of civil society? Might another eight-year cycle conclude ignominiously? Rationally, he told himself, there was simply not enough time for his opponents to get their act together before the general election took place on the Sunday following Easter. He would surely triumph, even if not with the magical two-thirds majority that allowed him in effect to ignore the parliamentary opposition. But the well-organized campaign to unite voters against his party in the name of a new “system change” left him more seriously rattled than he had ever been before. Even if he won this Easter, what would happen in four years’ time, and what could he expect at every single by-election in the meantime? One morning, Viktor woke up with feverish premonitions, after dreaming that he was a dragon, severely wounded by the redoubtable wizard called George.