There is a failure here that topples all our success. The fertile earth, the straight tree rows, the sturdy trunks, and the ripe fruit. And children dying of pellagra must die because a profit cannot be taken from an orange. – John Steinbeck

Midway through The Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck turns away from the dispossessed Joad family to consider the injustice of a farm system that values profit over a flourishing rural economy. The coronavirus pandemic has disrupted local food economies and supply chains, and these disruptions have been centuries in the making: beginning with the privatization of commons, settler colonialism, redistribution of labor, and efforts to intensify the capitalization and technification of agricultural work. Like any agrarian crisis, the pandemic reveals cracks and opportunities amid hegemonic order (Flachs 2021). Although all stakeholders want to shift labor and production, their post-pandemic visions for the future differ: some advocate for an agrarian degrowth, yet others see the pandemic as a chance to better position themselves in a post-COVID hierarchy.

Food Regime (Friedmann and McMichael 1989) and Capitalocene (Moore 2015) analysts roughly agree in seeing agrarian capitalist crises emerging from industrializing Europe (Araghi 2000; Kautsky 1988) as a combination of colonialism and enclosure. As land in the colonial periphery was made cheap and exploitable, common land and labor relationships were severed back in the metropole through a slow process of privatization. In much of the world since the mid-20th century, farms became increasingly consolidated and production increasingly specialized as technology and capital appropriated discrete elements of farm production (Goodman, Sorj, and Wilkinson 1987).

Current pandemic-induced agri-food anxieties in the US stem from a century of agrarian change that has embraced productivism: the ideology that production yields and profit growth are and should be the key drivers of agriculture (Buttel 1993). In the decades following the Great Depression, US farm sizes have steadily increased while the number of individual farms has plummeted (Magdoff, Foster, and Buttel 2000), destabilizing land tenure, work, and rural institutions (Goldschmidt 1978).

Alternative food networks are common responses to acute economic crisis: Americans flocked to vegetable gardening during the first and second world wars (Lawson 2005), civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer organized America’s largest farm cooperative in response to the eviction of Black tenant farmers across the American South in the 1960s (White 2018), and Americans returned to urban gardens in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis (Flachs 2010; Poulsen et al. 2014). Shaken by shortages and price hikes at grocery stores, Americans rushed to buy vegetable seeds and garden supplies during the first waves of the pandemic, but they also supported an explosion of interest in local food through farmer’s markets, farm shares, and food deliveries.

To understand how local farmers responded to this sudden uptick in interest, we recruited farmers and farm managers as part of a larger, long-term project led by Dr. Ankita Raturi on data management and resilience in the local food system. Thanks to support from the Social Science Research Council’s Just Tech Covid-19 Rapid-Response program, we interviewed 12 local food coordinators and 29 Midwest farmers across rural, periurban, and urban environments to map the flows of information and food before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Growing Local Food

Farmers across the Midwest experienced the pandemic as a time of growth and expansion. “People were going to stores and they were out of meat, so it became this scramble: where can I get meat,” explained a rural Indiana beef farmer. “[It] opened their options a little bit more…We hear from some of our new customers that, ‘wow this is great!’ We didn’t know you were here this whole time and now we buy from you every other week.” Similarly, an urban herb and vegetable farmer laughed when we asked how his business coped with COVID-19. “Everything was booming through the roof…I don’t want to sound harsh, but the pandemic was good for farmers.” Growth is a desired goal here, outpacing the low-scale, high diversity local farms from before the pandemic. “This is the year of simplicity,” explained an urban farmer. “We don’t have 1,001 products; we specialize in 10-20.” Local farmers turned to their data collection as demand grew and began asking where they could save time. “I really focus on how to reduce labor costs,” explained a periurban orchard manager. “Are there ways that I can automate in those areas or at least use tools or make a mechanical means to reduce labor and time spent?” Guthman (2004) called this creep toward agrocapitalist logic conventionalization, to note how alternative organic agriculture came to resemble industrial farming. Here, we observe that this is also as a growth trap and a data organization issue: conventionalization manifests as a combination of labor shortage, intensified demand, opportunism, and digital nudges implicit in data monitoring.

After initial hesitation over social distancing and public health, farmer’s markets and local food distributors across the country sprang back with new safety protocols and tools to arrange local food pickups. Market managers also saw upticks in consumer interest in local food and especially in local meat. One such program became especially popular in Indiana and later across the Midwest as a tool to aggregate local food in regional cities and then deliver directly to consumers. The founder, himself a participating farmer, recalled:

[The stay-at-home order] hit and that Saturday we did as much volume that day as we would usually do in an entire week… Monday, we were freaking out. We did 400% volume that week and we thought: alright, let’s figure out how to just survive this week, we don’t have the shelf space or anything, but the vendors were there… We bought every black insulated tote east of the Mississippi that we could find.

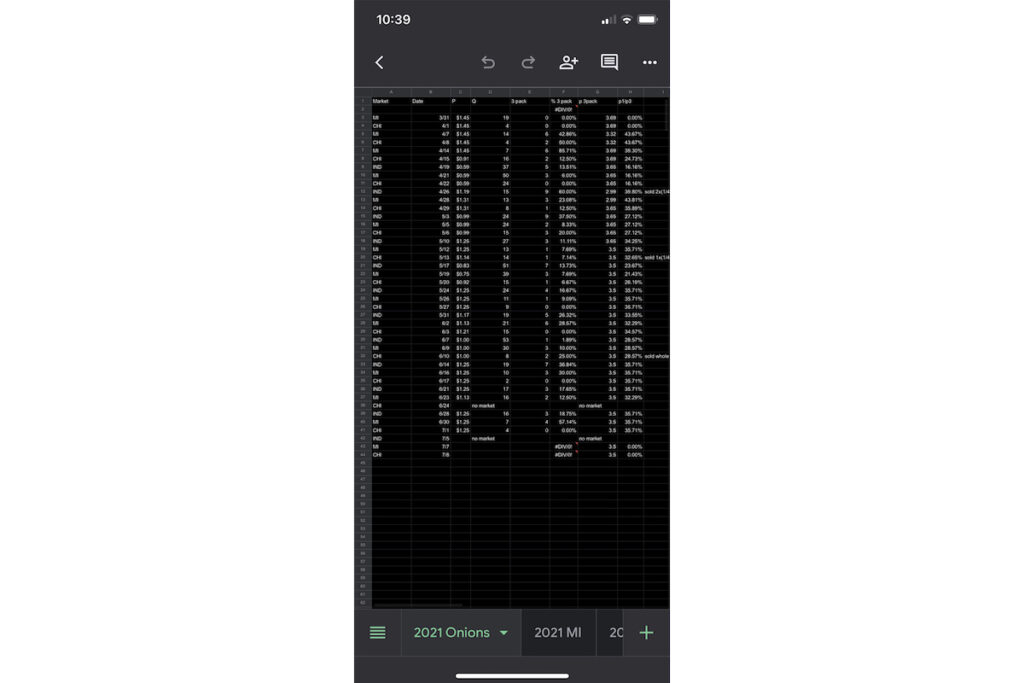

Nine months into the pandemic, the program expanded from six to 32 cities, a sign of the enduring demand for local food deliveries that circumvent grocery store supply chains. Critical scholars of science and technology have shown how the forms people use to organize information also dictate future planning (Ballestero 2019; Benjamin 2019). Produce demand grew alongside data management including spreadsheets, social media communications, and shifting inventory ledgers. Seeing these spreadsheets, many Midwest local farmers struggled to grow their production, ultimately paring back the diversity of food and services they offered.

Degrowing Local Food

Others looked over their data to find that their work, and the sociocultural values underpinning it, needed reexamining after March 2020. Degrowth, a political-economic theory of reorganizing production to achieve socio-ecological sustainability over the long term (Gerber 2020; D’Alisa, Demaria, and Kallis 2015), provides a framework to evaluate the lasting impact of persistent local farming beyond the production or sale of agricultural commodities. By questioning externalized costs, capitalization, and yield growth in small farmer economies, degrowth asks how alternative rural development programs enable a range of possible futures on farms beyond continual expansion. Conversely, agriculture forces degrowth to face difficult questions around labor, productivity, and technological change – local food systems confront challenges in equitable labor and resource management in that they depend on difficult work and local ecological constraints. Scholars have looked to cases spanning Cuban agroecology (Boillat, Gerber, and Funes-Monzote 2012), Via Campesina (Roman-Alcalá 2017), and European allotment gardens (Vávra, Smutná, and Hruška 2021), questioning what an agricultural system might value apart from growth (Gerber 2020). Some Midwestern local food workers, having experienced the pressures of rapid growth, offer another perspective.

As employers cut hours for off-farm work, many farmers responded by intensifying their farm businesses – not merely to recoup lost wages but also to finally pursue more meaningful work. “As much as it was frustrating and difficult, and horrible, and terrifying, it has really given us time that we needed to put everything in perspective,” explained an automotive industry engineer whose plant closed during the initial COVID-19 shutdown. “We did definitely arrive at a place where people [realized] I have all of this extra time but I’m not feeling like I have something fulfilling to do,” agreed a rural Wisconsin farmer. “I think labor is often talked about in the ag circle as something to reduce down to nothing. And I think that we need to flip that completely on its head … I think that the sort of stuff we’re doing can be a healthful meaningful activity.” Similarly, a periurban orchard grower delved into his data not to specialize in top sellers but to understand how to turn buyers on to rare or unusual varieties. “My wife is an educator, my father is an educator, my grandfather was. We just enjoy doing that sort of thing,” he explained. “We also need probably 7 or 8 varieties because a part of the educational aspect of this, which I dearly love, is helping people select the apple that they enjoy.”

Others explicitly saw their agricultural work as a path toward social justice. “I know that my price points are not all that low because I have a high input cost. But… it costs a lot of money to heal this planet,” a rural Minnesota farmer explained. She plans to continue this healing process by donating her farm to Indigenous or Black female farmers when she retires as a form of reparation for centuries of systemic racism in American agriculture. “It’s really hard I think to figure out how to do reparation on a system level. But on a one-sie, two-sie level I can make that happen.” For an urban hydroponic farmer, growing vegetables in a shipping container was an explicit response to the generational marginalizing of Black farmers that stems from “not having access to land. I don’t have access to seven acres of land to try to grow lettuce. So, pivot and do something different…If you don’t have fertile land that plants like, and that you can grow plants in, and that has that nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium that plants need, you’re just wasting your time. And most people that look like me don’t have access to that kind of land that’s suitable for plant growth.” Amid questionable, data-driven indoor agriculture expansions over the last decade, this farmer highlighted the role that indoor agriculture can have in bringing equity to local food production.

Building and Degrowing in the Post-Corona Rural Economy

Anthropological insights should always tie to lived experiences of particular times and places, not universalist theories bent to match interesting case studies. No farmers discussed wanted to produce less. However, a degrowth perspective on agricultural sustainability is not inherently against all increases, but rather against a particular model of short term extraction (D’Alisa, Demaria, and Kallis 2015; Gerber 2020) that imagines rural economies as short term assets to be leveraged and then liquidated in the mode of financial capitalism. When the Midwestern local food economy experienced rapid growth, some took it as a sign to intensify production and compromise on biodiversity and employment – but many were cautious to pursue goals of diversification and meaningful work, eschewing growth that came at the expense of solidarity and ecological commons.

Smallholder theory building from A.V. Chayanov (1966) and Robert Netting (1993) offers a general model wherein farmers often want to expand their sales, group memberships, savings, and production, because it helps them to escape difficult work, subsidize risks, and build a promising future in their own terms. Historically, crises of political economy have opened doors for temporary exercise of radical politics as seen during the resurgence of US urban gardens through war and financial crises and the organization of Black farmer cooperatives in response to civil rights activism and white agrarian closure in the US South. As they grew into internationally regulated brands, organic and Fair-Trade initiatives succumbed to conventionalization as they adopted productivist logics and ultimately aimed to increase yields, profits, and consumption. Clearly, some of the farmers above are taking this opportunity to expand into new markets. Yet others seek not an expansion of sales or production so much as an expansion in labor, skill, education, or equity. As a moment to challenge agri-food hegemony, the pandemic allows these farmers to pursue these goals above sheer growth. Such work is sorely needed to reorient food systems toward the kinds of collective solidarity and local investment necessary to provide a future in which US farmers and their farms can diversify away from extractive monoculture farming underwritten by the violence of cheapened labor. The efforts that farmers and farm supporters make now to manage renewed interest in local food economies is having serious repercussions for rural, urban, and peri-urban farm economies moving forward. Equal attention should be paid to how these changes ultimately reflect what kind of lives people want to live on the farm.

Andrew Flachs researches food and agriculture systems, exploring genetically modified crops, heirloom seeds, and our own microbiomes. An associate professor of anthropology at Purdue University, his work among farmers in North America, the Balkans, and South India investigates ecological knowledge and technological change in agricultural systems spanning Cleveland urban gardens and Indian GM cotton fields. Andrew’s research has been supported by public and private institutions including the Department of Education, the National Geographic Society, the American Institute of Indian Studies, and the Volkswagen Foundation, while his writing on agricultural development has been featured in numerous peer-reviewed publications as well as public venues including Sapiens, Salon, and the National Geographic magazine. Andrew’s work has been recognized by numerous international awards, including most recently the Political Ecology Society’s Eric Wolf Prize and the International Convention of Asia Scholars’ Book Prize Committee.

Ankita Raturi is an assistant professor at Purdue University, where she runs the Agricultural Informatics Lab, focused on human computer interaction, information architecture, and software engineering, for increased resilience in food and agricultural systems. Ankita’s current work includes: the development of modular, open source, decision support tools (e.g., for cover cropping); information modeling for the development of agricultural ontologies and data services(e.g., for plant data); design methods for agricultural technologies (e.g., for soil health management technologies); and design for diversified farming systems (e.g., for community food resilience).

Juliet Norton is an Informatics Research Scholar in the Department of Agricultural & Biological Engineering at Purdue University working with Ag Informatics Lab. She is a co-project manager for the NECCC Cover Crop Species Selector Tool and Seeding Rate Calculator, MCCC Seeding Rate Calculator, SCCC Species Selector Tool, and Informatics for Community Food Resilience projects. She works remotely from her home in Martinez, CA. http://aginformaticslab.org/index.php/2020/04/15/juliet-norton/

Valerie Miller is a PhD candidate and graduate teaching assistant in the anthropology department at Purdue University. She holds an MA in applied experimental psychology. Now studying as abiocultural anthropologist, she researches alloparenting, postpartum experiences, maternal cognition, and mental health in the United States and the Commonwealth of Dominica. Valerie is trained in several ethnographic and psychological methodologies, both qualitative and quantitative, and integrates these approaches while researching human matrescence, cognition, and lifeways of Caribbean women. She is passionate about highlighting maternal perspectives within biocultural research projects as well as the centering of children’s voices and insights in ethnographic studies. Her writing has been published in peer-reviewed journals as well as public-facing online spaces including Teaching Anthropology and Ethnography.com.

Haley Thomas is an undergraduate at Purdue University pursuing a bachelor’s degree in agricultural engineering. She is working with Agricultural Informatics Lab to study farmers’ data management and software for local foods. Her other academic interests include ecological restoration and natural resource management. http://aginformaticslab.org/index.php/2021/07/15/haley-thomas/

References

Araghi, Farshad. 2000. “The Great Global Enclosure of Our Times: Peasants and the Agrarian Question at the End of the Twentieth Century.” In Hungry for Profit: The Agribusiness Threat to Farmers, Food, and the Environment, edited by Fred Magdoff, John Bellamy Foster, and Frederick H Buttel, 145–60. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Ballestero, Andrea. 2019. A Future History of Water. Illustrated edition. Durham: Duke University Press Books.

Benjamin, Ruha. 2019. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. 1 edition. Medford, MA: Polity.

Boillat, Sébastien, Julien-François Gerber, and Fernando R. Funes-Monzote. 2012. “What Economic Democracy for Degrowth? Some Comments on the Contribution of Socialist Models and Cuban Agroecology.” Futures, Special Issue: Politics, Democracy and Degrowth, 44 (6): 600–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2012.03.021.

Buttel, Frederick H. 1993. “Ideology and Agricultural Technology in the Late Twentieth Century: Biotechnology as Symbol and Substance.” Agriculture and Human Values 10 (2): 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02217599.

Chayanov, A. V. 1966. The Theory of Peasant Economy. American Economic Association Translation Series. Homewood, Ill: Published for the American Economic Association, by R.D. Irwin.

D’Alisa, Giacomo, Federico Demaria, and Giorgos Kallis. 2015. Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era. New York: Routledge.

Danovich, Tove. 2020. “With Social Distancing, CSAs Are Trending as a Way to Shop for Groceries.” Eater, April 2, 2020. https://www.eater.com/2020/4/2/21200565/csa-trend-coronavirus-covid-19-stay-at-home-delivery-groceries.

Flachs, Andrew. 2010. “Food For Thought: The Social Impact of Community Gardens in the Greater Cleveland Area.” Electronic Green Journal 30 (1): 1–9.

Flachs, Andrew. 2021. “Charisma and Agrarian Crisis: Authority and Legitimacy at Multiple Scales for Rural Development.” Journal of Rural Studies 88 (1): 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.10.010.

Flachs, Andrew, and Matthew Abel. 2019. “An Emerging Geography of the Agrarian Question: Spatial Analysis as a Tool for Identifying the New American Agrarianism.” Rural Sociology 84 (2): 191–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12250.

Friedmann, Harriet, and Philip McMichael. 1989. “Agriculture and the State System: The Rise and Decline of National Agricultures, 1870 to the Present.” Sociologia Ruralis 29 (2): 93–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.1989.tb00360.x.

Gerber, Julien-François. 2020. “Degrowth and Critical Agrarian Studies.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 0 (0): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2019.1695601.

Goldschmidt, Walter Rochs. 1978. As You Sow: Three Studies in the Social Consequences of Agribusiness. Montclair: Allanheld, Osmun & Co.

Goodman, David, Bernardo Sorj, and John Wilkinson. 1987. From Farming to Biotechnology: A Theory of Agro-Industrial Development. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Guthman, Julie. 2004. Agrarian Dreams: The Paradox of Organic Farming in California. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Guthman, Julie. 2017. “Willing (White) Workers on Organic Farms? Reflections on Volunteer Farm Labor and the Politics of Precarity.” Gastronomica: The Journal of Critical Food Studies 17 (1): 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1525/gfc.2017.17.1.15.

Kautsky, Karl. 1988. The Agrarian Question: In Two Volumes. Translated by Pete Burgess. London ; Winchester, Mass: Zwan Publications.

Lawson, Laura J. 2005. City Bountiful: A Century of Community Gardening in America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Magdoff, Fred, John Bellamy Foster, and Frederick H. Buttel, eds. 2000. Hungry for Profit: The Agribusiness Threat to Farmers, Food, and the Environment. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Moore, Jason W. 2015. Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital. New York: Verso.

Netting, Robert McC. 1993. Smallholders, Householders: Farm Families and the Ecology of Intensive, Sustainable Agriculture. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Olson, Kathryn A. 2019. “The Town That Food Saved? Investigating the Promise of a Local Food Economy in Vermont.” Local Environment 24 (1): 18–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2018.1545753.

Poulsen, Melissa N., Kristyna R. S. Hulland, Carolyn A. Gulas, Hieu Pham, Sarah L. Dalglish, Rebecca K. Wilkinson, and Peter J. Winch. 2014. “Growing an Urban Oasis: A Qualitative Study of the Perceived Benefits of Community Gardening in Baltimore, Maryland.” Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment 36 (2): 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/cuag.12035.

Ricker, Hannah, and Mara Kardas-Nelson. 2020. “Community Supported Agriculture Is Surging Amid the Pandemic.” Civil Eats, April 9, 2020. https://civileats.com/2020/04/09/community-supported-agriculture-is-surging-amid-the-pandemic/.

Roman-Alcalá, Antonio. 2017. “Looking to Food Sovereignty Movements for Post-Growth Theory | Ephemera.” Ephemera 17 (1): 119–45.

Vávra, Jan, Zdeňka Smutná, and Vladan Hruška. 2021. “Why I Would Want to Live in the Village If I Was Not Interested in Cultivating the Plot? A Study of Home Gardening in Rural Czechia.” Sustainability 13 (2): 706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020706.

White, Monica M. 2018. Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement. UNC Press Books.

Cite as: Flachs, Andrew, Ankita Raturi, Juliet Norton, Valerie Miller, and Haley Thomas. 2022. ”Building back bigger or degrowing local food? US alternative food networks and post-corona agrarian economies.” FocaalBlog, 23 March. https://www.focaalblog.com/2022/03/23/andrew-flachs-ankita-raturi-juliet-norton-valerie-miller-and-haley-thomas-building-back-bigger-or-degrowing-local-food-us-alternative-food-networks-and-post-corona-agrarian-economies