Tiny bodies, the remains of little children entombed without name or mercy, are uncovered in Tuam, a small Irish town in Co. Galway in the west of Ireland, at the site of a former Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home in 2017. The excavation, part of a Mother’s and Baby’s Home commission of inquiry (set up in 2015), precipitated by the tireless research of a local historian Catherine Corless, uncovered an eerie underground structure demarcated into 20 chambers (possibly a sewage tank) containing the children’s remains. The commission stated that ‘multiple remains’ were found, but some estimates run as high as in the region of 800. The home was run by the Catholic Bon Secours order of nuns from 1925 to 1961, one of many on the island of Ireland at that time. Now in Oct 2020, even before the Commission of inquiry publishes their long-delayed report (original deadline Feb 2018 due now Oct 30th, 2020), the Irish State has stated it intends on sealing the Mother and Baby records for 30 years.

Continue readingMonthly Archives: October 2020

Janne Heederik: The Voluntarisation of Welfare in Manchester: A Blessing and a Burden

This post is part of a feature on “Urban Struggles,” moderated and edited by Raúl Acosta (LMU Munich), Flávio Eiró (Radboud University Nijmegen), Insa Koch (LSE) and Martijn Koster (Radboud University Nijmegen).

As a result of welfare reform and continuing budget cuts, social service agencies in the UK have struggled to make ends meet and match the still-growing demand on their services. Local councils and the voluntary sector have both suffered cuts. The former are increasingly looking to the voluntary sector for help, while the latter used to rely heavily on grants from statutory bodies and suffers from increased funding restrictions. In the context of welfare reform, a model of active citizenship and participation has emerged. This model focuses on decreasing citizen dependence on welfare and social services while encouraging the ‘responsibilisation’ of citizens (Verhoeven & Tonkens, 2013). This policy agenda, supported by successive UK governments, has painted a picture of the ‘active citizen’ as a solution and improvement to the budget cuts in the voluntary sector. Citizens are encouraged to ‘take more responsibility’ instead of ‘depending on remote and impersonal bureaucracies’. As part of this responsibilisation, volunteers have taken center stage and their positive impact on communities is emphasized and celebrated (Schinkel & Van Houdt, 2010). Volunteers play an increasingly crucial role in welfare provision and the welfare system relies heavily on their work.

The extent of this reliance became clear during my fieldwork in Manchester in 2018 – 2019. I conducted ethnographic fieldwork in Manchester for 16 months, during which I worked with several advice centers in Greater Manchester. In November 2018, I attended a ‘Volunteer Day’ organized by the advice center I had been volunteering at for the past year. This annual event celebrates volunteers and gives paid staff and management a chance to thank volunteers for their work and commitment. The day was opened by a speech from Jack Puller, member of the charity Manchester Alliance for Community Care (MACC), who ‘supports and encourages local people to be active citizens through volunteering and other forms of participation’. His speech focused on impact and how to measure it. In numbers, he states that more than 110,000 people in Manchester volunteer, putting in a total of 278,000 hours of work each week, and having a total worth of 252 million pounds. Puller also mentioned that impact cannot be measured in numbers alone. Volunteers are vital to social services, arguing that they reflect the spirit of Manchester and are crucial to the existence of places like the advice center.

While this still presents a positive image of the impact of volunteering, the reality is that many advice centers can no longer survive without volunteers and there is a constant need for more volunteers to fill the gaps in advice services. Advice centers, along with other social services, have suffered from a ‘double squeeze’: a withdrawal of public services has led to an increase in demand, while they simultaneously have to work with shrinking budgets (Evans, 2017). As a result, many depend on the work of volunteers more than before and even then, many fail to meet the demand and have to send people looking for their help away on a daily basis, as I experienced during fieldwork. Voluntarism in British welfare provision is thus not as straightforward and romantic as Puller depicted it, and both volunteers and paid advisers often struggle to navigate their workload and the relationship between them. The double squeeze on advice centers has not only made them more dependent on volunteers but has also changed the role of volunteers, who have become central more in the advice centers. In this contribution, I further analyze how the dependence on volunteers has changed their role within advice centers, showing how this affects the relationships between paid advisers and volunteers and analyzing how narratives of active citizenship often translate into different realities. Specifically, I lay bare how a politics of austerity has resulted in a paradoxical relationship with volunteers, where they are perceived as both a blessing and a burden.

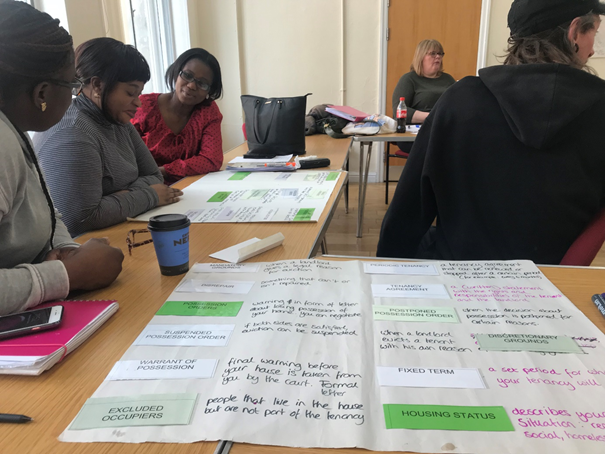

Many social services, including advice centers, have aimed to bridge the growing gap between demand and capacity by relying more heavily on the work of volunteers, with some advice centers I worked with even being completely volunteer-run. This gap is usually characterized as a gap in more professional work, where paid advisers can no longer cover all their tasks due to lack of time and resources. As a result, the growing reliance on volunteers in the provision of social services is also characterized by the increasingly professional nature of the work volunteers do. As Verhoeven and Bochove note, volunteers are now expected to do more than provide complimentary work to the work paid advisers do, they are increasingly expected to take over parts of the paid advisers’ responsibilities, referred to as the ‘volunteer responsibilisation’ (Verhoeven & Van Bochove, 2018). However, my fieldwork showed that many volunteers are underprepared when they first start their work and are not able to carry out those responsibilities, which complicates the working dynamics at the center. At an advice center in the North of Manchester, where about two thirds of staff members are volunteers, all prospective volunteers must attend a training program to prepare them for volunteer responsibilities. I volunteered here as well and attended the 9-week training program, with one training day a week. The training aimed to prepare volunteers for both the practical and emotional labor ahead of them, but often proved insufficient once volunteers started their voluntary activities at the advice center. The large majority of volunteers felt underprepared for the complexities and intensities of advice work. For example, a former volunteer named Susan told me that she enjoyed helping clients with more straightforward form-filling, but struggled with more complex cases. For her, it resulted in high levels of anxiety and guilt, to the extent that she eventually stopped volunteering as an adviser. ‘It felt like I was just sitting there with my hands cut off, watching someone in front of me die’, she told me.

Welfare advisers often have to deal with difficult and complex situations, with their clients struggling to make ends meet and often coming to the advice center feeling desperate and upset. It is the task of advisers to guide their clients through the welfare system, approach authorities on their behalf, and manage benefit outcomes to their best ability. However, the welfare system has grown increasingly complex, and advisers often have to engage in a ‘complex web of relations’ to assist their client (Forbess & James, 2014:80). For volunteers like Susan, the practical skills and emotional labor required to do good advice work, often feel like too big a responsibility to carry. Similarly, during my time as a volunteer at this advice center, I had to help clients who were about to be evicted, clients who had lost all their income, clients who had escaped abusive relationships, and clients who were depressed and sometimes even suicidal. While the training program provides basic information on how the welfare system operates and how advisers navigate it, these intricacies of advice-giving are too complex to teach in a course. Many volunteers, like Susan, are in need of more guidance, but more often than not volunteers are thrown into the deep-end and have to cover tasks previously done by professionals. Unlike their paid colleagues, however, they have to do without the financial or practical support: they do not receive monetary pay, nor do they receive the proper training to teach them how to deal with the complex client cases and the emotional labor that comes with it. In addition, the high demand and the lack of space, time, and resources, means that there is little time to process such events. Volunteers I spoke to often felt alone in dealing with some of the hardship they were faced with when seeing clients. One volunteer described how he often felt inadequate and how this resulted in him researching ongoing developments and policy changes at home:

I feel like I am always at the limits of my knowledge, and I already know a lot more than the average person. Volunteers like me have to put in a lot of time. You don’t just do your hours here. I often have to research stuff at home too.

Whilst active citizenship is thus envisioned as an enriching and fulfilling experience, for many volunteers this is only part of the story. The work they take on is more intense and demanding then initially anticipated and some volunteers struggle with the pressure they feel to respond to the demand adequately. These high expectations of volunteer work and the contradictory lack of training and preparation imply that volunteers can no longer be seen as amateurs supporting social services, but as professionals who deliver unpaid yet essential work (Coule & Bennett, 2018; Verhoeven & Van Bochove, 2018). It is an attempt for voluntarism to strengthen the welfare system despite reform and budget cuts, but it falls short in its assumption that welfare advice can be done by anyone at any time.

Advice centers thus need volunteers to fill certain gaps in their work capacity, but at the same time struggle with the knowledge that volunteers often cannot fill these gaps with the same level of professionalism as paid advisers. Volunteers often turn to paid advisers for both practical and emotional support. Advisers might have to jump in or even take over appointments from volunteers who are unable to help their clients sufficiently. The manager of one of the advice centers expressed her concern regarding the center’s reliance on volunteers, stating it worried her that ‘this type of work is done by volunteers. Such overly complicated issues like almost all benefit cases rely on volunteers’. She worried for the clients, who might not get the right help if volunteers tried to solve client’s cases on their own, but was equally worried about volunteers and whether they were able to cope. Furthermore, often having to rely on assistance from paid advisers, the use of volunteers within advice centers often leads to an increase in workload for paid advisers. This leads to a paradoxical situation, where advisers must rely on volunteers for the survival of the advice center, but at the same time experience an increase in their workload as many volunteers need guidance and training.

This paradox is further complicated by the fact that relying on volunteers always comes with certain levels of insecurity as volunteers are not bound to contracts and employment conditions like paid advisers are. The turnover of volunteers was high at all the advice centers I visited, with volunteers staying anywhere between weeks and months, but rarely longer than a year. Additionally, coming from a wide variety of backgrounds, volunteers often had a wide range of skills and abilities, meaning not every volunteer could handle the same tasks and paid advisers spent a lot of time figuring out what volunteer would cover which task.

For permanent staff and management, relying on volunteers is thus necessary for the survival of the advice center, but never easy. And it can at times be burdensome. Volunteers cannot fulfill certain roles and end up sitting around and doing nothing, while at the same time there is never enough staff to do everything that needs doing. As a result, staff end up having to spend more time helping volunteers then they might gain form their presence. This situation forces paid advisers to engage in ‘volunteer management’ (Verhoeven & Van Bochove, 2018). Volunteer management involves the dividing of tasks among volunteers according to their skills and abilities, keeping track of who will be present on what day and making sure volunteers are spread out evenly across the week, checking in with volunteers to make sure they can cope with the demand and emotional labor of their work, and assisting volunteers in their work whenever necessary.

In addition, volunteer management also impacts the relationship between volunteers and advisers. Dividing tasks among volunteers often resulted in an unequal distribution of tasks, where more highly educated or experienced volunteers would be given many and more complex tasks, whereas other volunteers struggled to get any tasks at all. During a volunteer meeting at one of the advice centers, volunteers had the chance to raise any questions or issues they had. One volunteer mentioned an incident where she had been asked to see a client, but she did not feel comfortable taking on the tasks as she felt unqualified to deal with the complexity of the client’s case. Another volunteer had offered to step in, but the adviser assigning the task would not listen. ‘I was essentially told to just get on with it’, the volunteer said, adding that it had made her feel very uncomfortable and hesitant to ask the adviser for any tasks in the future. Volunteers who were given more complex tasks mentioned that they often felt they were not prepared for the difficulties of these cases, and struggled to deal with them emotionally and practically. On the other hand, volunteers who struggled to stay busy, mentioned that they were bored, could not develop their skills, and felt they could not help as much as they had wanted to. The paradox of volunteers being both a blessing and a burden resulted in difficulties for paid advisers and volunteers and affected their relationship. However, despite having tensions in the workplace, where advisers sometimes feel volunteers just add to their workload and volunteers feel left to their own devices, these tensions did not seem to translate into frustration with one another. Volunteers were always acutely aware of the workload that paid advisers had to carry and understood that they simply lacked time to train volunteers. Furthermore, whilst being aware that as volunteers they sometimes added to this workload, volunteers said they felt respected and accepted by their paid colleagues. Advisers were always grateful and positive about the volunteers, highly aware of the advice center’s dependence on their work: ‘We would be closing our doors without them’, one adviser said. Similarly, the manager of the advice center stated: ‘Volunteers have played more and more of a key role, they are at the front of our service’.

However, the paradox of the volunteer as a blessing and a burden remains, and many advisers felt frustrated with their working conditions. Rather than resulting in frustration towards volunteers, this frustration was predominantly aimed at the government, and there was a strong sentiment that the government had failed the voluntary sector while at the same time having offloaded its responsibility onto citizens under the banner of active citizenship. The key issue advisers pointed to was almost always funding. As one adviser stated:

If they want this [advice work] to be free, they need to provide the proper funding […] Look at us, advisers can’t help you properly because they are busy with five other cases, volunteers are taking on responsibilities they shouldn’t be, and we are all overworked. And it’s the government that is to blame.

These tensions between advisers and volunteers are therefore more than workplace quarrels; they are political. They reflect the everyday reality on the frontlines of a policy agenda of budget cuts and ‘citizen activation’. The responsibilisation of voluntary work is therefore problematic not just in the heaviness of the responsibilities that volunteers have to carry and its effect on their relationship with advisers, it also lays bare the problematic nature of a policy agenda that aims to offload government responsibilities onto the voluntary sector and citizens, without providing them with the necessary financial assistance and substantive support. The experiences of paid advisers and volunteers tell a clear story: advice services – among many other social services in the UK – are in crisis, but as important as volunteers are, it should not be their role to rescue these services. However, the outcry for change is still predominantly focused on those they are trying to help: they protest and advocate for the rights of welfare claimants, and in the process forget to advocate for their own rights. Individual voluntary commitment can be a blessing, but the overall use of voluntarism as a solution to budget cuts and welfare reform is a burden.

Janne Heederik is a PhD Candidate in Anthropology and Development Studies at Radboud University and a member of a ERC-funded research project on participatory urban governance. Based on ethnographic research in Manchester, UK, her research explores welfare, poverty, and brokerage in contemporary Britain.

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 679614).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Coule, T., & Bennett, E. (2018). State-Voluntary Relations in Contemporary Welfare Systems: New Politics or Voluntary Action as Usual? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 47(4), 139–158.

Evans, S. (2017). A Reflection On Case Study One: The Barriers to Accessing Advice. In S. Kirwan (Ed.), Advising in Austerity: Reflections on Challenging Times for Advice Agencies (pp. 23–27). Bristol: Policy Press.

Forbess, A., & James, D. (2014). Acts of Assistance: Navigating the Interstices of the British State with the Help of Non-profit Legal Advisers. Social Analysis, 58(3), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2014.580306

Schinkel, W., & Van Houdt, F. (2010). The Double Helix of Cultural Assimilationism and Neo-liberalism: Citizenship in Contemporary Governmentality. British Journal of Sociology, 61(4), 696–715. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2010.01337.x

Verhoeven, I., & Tonkens, E. (2013). Talking Active Citizenship: Framing Welfare State Reform in England and the Netherlands. Social Policy and Society, 12(3), 415–426. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746413000158

Verhoeven, I., & Van Bochove, M. (2018). Moving away, toward, and against: How front-line workers cope with substitution by volunteers in Dutch care and welfare services. Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union, 47(4), 783–801. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279418000119

Cite as: Heederik, Janne. 2020. “The Voluntarisation of Welfare in Manchester: A Blessing and a Burden.” FocaalBlog, 2 October. http://www.focaalblog.com/2020/10/02/janne-heederik-the-voluntarisation-of-welfare-in-manchester-a-blessing-and-a-burden/