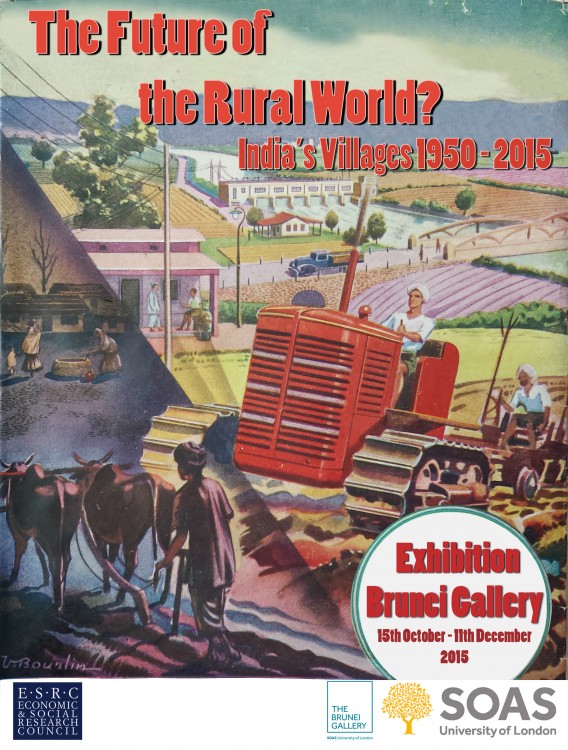

The conference “The Future of the Rural World? Africa and Asia” was hosted by SOAS, University of London during October 2015. The event marked the end of a major project funded by the United Kingdom’s Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) on “restudying” village India. It also coincided with the launch of an exhibition and film installations at the Brunei Gallery at SOAS, which emerged from the same project. At the conference, Peter Ho, Katy Gardner, and Henrietta Moore spoke provocatively on rural futures in China, Bangladesh, and East Africa.

Most of world’s scholarly and media attention is on megacities and the story of rapid urbanization they are held to represent. Slums have become photogenic and dramatic devices. However, the greater part of the world’s population continues to live in rural areas. This will continue to be the case for some time to come. The consequential and untold story, however, is the radical transformation of the countryside, as things formerly thought of as villages become something else. These places mark the emergence of a new form of settlements that are neither cities nor villages in the conventional uses of such terms. The language of social science is ill equipped for these new realities.

The aims of the original ESRC project had been straightforward: to conduct new fieldwork in villages where anthropological research had been undertaken in the 1950s in order to see what had changed.

Anthropologists who then made the voyage to India documented a sophisticated agrarian society ordered by caste and institutionalized inequality—where the division of labor mirrored the ritualized and hierarchical exchange relationships of caste. Today, their accounts form an unprecedented and intimate historical account of what life was like in villages during the heady years immediately after independence.

The world has changed. In India, Nehru’s socialism, strongly influenced by Cold War politics, has given way to the forces of (neo)liberalization and globalization. Waves of development policy have been unevenly implemented across the country; political devolution has passed some responsibility for economic development, social justice, and taxation to the village level; affirmative action ushered in caste-specific and gendered “reservations.” Land reforms and new technologies have transformed agriculture, while public health programs enhanced children’s chances of survival. Nehru’s ghost has been exorcised by neoliberalism.

In the United Kingdom in the first half of the 1950s, the original anthropological studies were undertaken independently by F.G. Bailey, Adrian C. Mayer, and David F. Pocock (1928–2007). The three went on to have distinguished careers as exponents of the postcolonial sociology of India. The villages they studied are now located in the modern states of Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, and Gujarat. All three locations display legacies of postcolonial development and political policies, consequences of economic and land reform or consolidation, and effects of technological and media expansion. In each location, there has been a clear growth of grassroots Hindu nationalist sentimentality, as well as a hardening of religious and ethnic lines. The salience of caste is less but remains significant. Rural populations have grown between three and five times in size in the last sixty years.

What emerges most strongly from this project, however, is just how diverse rural futures are. The trajectories of three of India’s 600,000 or so villages tell of quite divergent scenarios.

Going back further in time for a moment, the Indian village has played a surprisingly important role in global theories of history and politics, both conservative and revolutionary. Over the centuries, the village has been comprehensively used and abused, a site for fantasy of both the left and right, for liberals, mythologists, and pundits. The idea has become a vessel into which all manner of political ambition has been poured. Maine, Marx, Engels, and Weber all had something to say on the significance of rural life in India.

In the nineteenth century, Imperial arguments were made for economic liberalization on the basis of customary inequalities and modes of property ownership reported in villages. For many radicals, in contrast, the village community exemplified qualities of life, such as liberty, equality, and fraternity—all of which had been realized in some past époque or were realizable in some future utopia, but significantly, these qualities were currently at risk.

All in all, the village community occupied a painfully ambiguous position, symbolizing the world European men had lost, a profoundly nostalgic view of an alternative society, which could be compared with the present for signs of both progress and degeneration.

This seems to remain the case today in India. The village remains on the brink of being lost forever, but it has been for at least two centuries, possibly longer. Village realities have changed, of course, but the way the village is situated as tangible but threatened remains. In the 1950s, it was quite clearly documented that the village was in the midst of radical change. Universal suffrage in 1950 was perhaps the single biggest event because suddenly villagers mattered to the politics of the nation in ways they had never been before.

At the time, Bailey, Mayer, and Pocock saw that farming could no longer form the backbone of the village economy; new technologies, population pressure, and the seep of the cash economy spelled the inevitable decline of agriculture. They also saw that there would be an increase in other forms of employment, along with a corresponding shift in traditional patterns of hierarchy and inequality. The influence of land, at least on the scale of the village, was inevitably to lose ground to commercial acumen and cash wealth.

Since that time, remarkably similar conclusions have also been the repetitive key findings of six decades of rural studies, in India but also elsewhere. The countryside has been hollowed out, farming has ceased to provide an income for most, and dirty fingernails have gone out of fashion.

Today, in Orissa, land rights and tribal identities have become burning issues, as people have been brought into conflict with transnational corporations and rapacious extractive industries. However, the village remains recognizably as it was in the 1950s; those who survive from that time display more wrinkles for the camera, but their rituals and concerns remain similar.

Rapid industrialization in Madhya Pradesh has brought villagers into wage relations with India’s industrial houses. A new highway has sucked the core of the village out of the hinterland and closer to the tarmac and city. A surprising number of people who were not born in the village now live there, some of whom have come from far away. A formerly impoverished Muslim population has become politically dominant.

In Gujarat, the village has become more firmly part of the transnational networks and nostalgic and nationalist politics of migrants in East Africa and the United Kingdom. Violence in the state in 2002 saw minarets demolished; most Muslim residents subsequently decided they would be safer elsewhere.

Life in these villages is clearly not the same as it was in the 1950s.

Some suggest the village has become a “waiting room” for industrial labor markets; for others the village has withered or even died. What has emerged has been described as an urban-rural continuum. Other neologisms (some of which are no longer that new) include, peri-urban, ex-urb, the fringe city, vicinities or vicinage, and hermaphroditic and in-between sprawl: the rurban!

The ESRC project allowed the luxury of looking and thinking backward in time. The juxtapositions we came to face to face with encouraged us to identify trends and trajectories, and eventually brought us to our question: the future of the rural world?

The initial findings of our research once again echo those already glossed from the literature: agriculture has crumbled, livelihoods have diversified, mobility is endemic, and so forth. Mass unemployment, “over” education, and cultures of “waiting” are endemic. Religion dominates public discourse in many locations. Land fragmentation is combined with speculative land and construction markets. Private monopolists dominate many local supply chains. Transnational capital has become increasingly sophisticated at extracting revenue. Service professions and a middle class have entered rural life. A mobility paradigm organizes daily and life-cycle expectations for many.

However, instead of seeing these as catastrophes marking the end or degeneration or pollution of the world as we know it, our longitudinal perspective shows that these are in fact the ongoing processes at the heart of continuing to negotiate what it means to live in a village. To put it simply, these are the things of a village way of life, which have accelerated village modernities in different ways in the three sites.

Overall, I suggest that city-dominated knowledge, the urban bias so naturalized in common thought and long highlighted by scholars such as Michael Lipton, has turned rural India into a bloodstained battleground of planning and land deregulation, transecting and gated highways, developer bandits, windy electricity, fields of photolytic cells, and mineral extraction. Today’s paddy is tomorrow’s gated community or global township. Predatory capitalism and private monopolists run wild, as local economies are buoyed by speculative land investment and boom and bust spirals. The future looks rather grim, at least in some parts of what was once rural India.

Edward Simpson is Professor of Social Anthropology at SOAS, University of London. He is the author of The political biography of an earthquake: Aftermath and amnesia in Gujarat, India (Hurst, 2013). He was Principal Investigator on the ESRC award referred to in this blog and is PI on an ERC-funded project looking at infrastructure development in South Asia.

Cite as: Simpson, Edward. 2015. “The future of the rural world?” FocaalBlog, 8 December. www.focaalblog.com/2015/12/08/edward-simpson-the-future-of-the-rural-world.